ISSN: 1705-6411

Volume 4, Number 3 (October 2007)

Author: Dr. Leslie S. Curtis1

The word ‘art’ bothers me…2

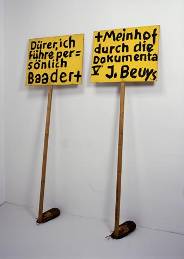

The title of this essay is derived from Joseph Beuys’s “Dürer, I will personally lead Baader + Meinhof through Documenta V” (1972), which resulted from his encounter with the action artist Thomas Peiter, who spoke briefly at the opening press conference for Documenta V and went around the exhibition dressed as Albrecht Dürer. In this guise Peiter visited the space that Beuys inhabited during those 100 days – the Information Office of the Organization for Direct Democracy through Referendum – where Beuys would engage in discussions with visitors. Beuys befriended Peiter and would address him as Dürer, and one day, he called out to him: “Dürer, I will guide Baader Meinhof through the Documenta V. Then they will be rehabilitated!”. It was Peiter who wrote some of these words (and signed Beuys’s name) on wooden placards that had been painted yellow, and Peiter walked around the exhibition carrying these signs. By omitting the last part of Beuys’s declaration, these signs might suggest that Beuys was sympathetic with the well-known

1. Peiter. Placard (Documenta V)

2. Joseph Beuys

Red Army Faction terrorists (the last of whom had, in fact, been apprehended just before the opening of Documenta that year). Later, these placards were placed in Beuys’s “office” space and, shortly after the exhibition closed, Beuys added the felt slippers, and placed margarine and rose stems within them.3

I wish to emphasize that my title is not meant as a form of disrespect to Jean Baudrillard, even though I recognize that there are those who feel that Baudrillard might have benefited from some guidance in his approach to the art world. I do acknowledge that my title, like the words in Beuys’s title, could be misleading. On one level, the title derives from having been invited, shortly after Baudrillard’s death in March of 2007, to participate in a conference that would be taking place a few days before the opening of the international art fairs. Thus, if Baudrillard was leaving this world at a moment when all of the stars were lining up for that once in a decade occurrence when Kassel’s Documenta, the Venice Biennale, and Münster’s Sculpture Project would all coincide, there was an opportunity to consider Baudrillard’s life and works, especially as related to the visual arts, in the context of the exhibitions where the art world supposedly takes stock of itself. Of course, in some ways, this idea is preposterous to those who have read Baudrillard, for he was hardly indifferent to these events, which he called “the large exhibitions where thousands attend and the crowd itself constitutes a kind of medium”.4 Indeed, he might even see such a moment where art attempts to stage its “disappearing act” as one where all “the stars are falling from the sky,” to refer to one of his favorite fables.5 Baudrillard even admitted, “that art, basically, is not my problem,”6 and has stated, “True, art is on the periphery for me. I don’t really identify with it. I would even say that I have the same negative prejudice towards art as I do towards culture in general”.7

However, from time to time, Baudrillard did comment on these events. In an interview with Ruth Scheps he noted: “I remember saying to myself after the 1993 Venice Biennial, that art is a conspiracy and even an “insider trading”: it encompasses an initiation to nullity and, without being disdainful, you have to admit that there, everyone is working on residue, waste, nothingness. Everyone makes claims on banality, insignificance; no one claims to be an artist anymore”.8 As his career developed, Baudrillard was increasingly unable to completely avoid the contexts of these big exhibitions. For example, he participated in a discussion at the end of the Venice Biennale in 2003,9 and he was scheduled to appear at the Frieze Art Fair in October of 2006 to engage in a discussion with Sylvère Lotringer, but alas, he ultimately could not attend.10

Some persons within the art world hold a strong disdain for Baudrillard, or at least for his comments about the visual arts. For example, Catherine David, the artistic director of Documenta X, omitted Baudrillard from her 700-page plus catalogue, which included writings by significant European theorists, including Maurice Blanchot, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Pierre Clastres, and even Paul Virilio.11 But her introduction to the Short Guide for Documenta X (which was distributed to the press), posed questions which could have been framed by Baudrillard (for indeed they seem to paraphrase some of his comments and to respond to his questions about the art world): “What can be the meaning and purpose of a Documenta today, at the close of this century, when biennials and other large-scale exhibitions have been called into question and often for very good reasons? It may seem paradoxical or deliberately outrageous to envision a critical confrontation with the present in the framework of an institution that over the past twenty years has become a Mecca for tourism and cultural consumption.” Nevertheless, she concludes that “the pressing issues of today make it equally presumptuous to abandon all ethical and political demands.” Then she continues, specifically naming Baudrillard:

In the age of globalization and of the sometimes violent social, economic, and cultural transformations it entails, contemporary artistic practices, condemned for their supposed meaninglessness or ‘nullity’ by the likes of Jean Baudrillard, are in fact a vital source of imaginary and symbolic representations whose diversity is irreducible to the near total economic domination of the real. The stakes here are no less political than aesthetic –at least if one can avoid reinforcing the mounting spectacularization and instrumentalization of ‘contemporary art’ by the culture industry, where art is used for social regulation or indeed control, through the aestheticization of information or through forms of debate that paralyze any act of judgment in the immediacy of raw seduction or emotion (what might be called ‘the Benetton effect’).12

On at least one occasion, in a section of Impossible Exchange, Baudrillard wrote about a work from Documenta X. He commented on Ein Haus für Schweine und Menschen (A House for Pigs and People), a collaboration between Carsten Höller and Rosemarie Trockel, which was in many ways the signature work

3. Höller and Trockel. A house for pigs and people

of David’s exhibition, or at least one of the most widely discussed in the press:

… we still play-act representation. A good illustration of this modern hoax was provided by the Kassel documenta of 1997 with the ‘Pigsty’ Installation. Reaching up on tiptoe to see over a fence, spectators look down on a pigsty, while a large mirror opposite allows them to see themselves observing pigs. Then they walk round the shelter and park themselves behind the mirror, which turns out to be a two-way mirror through which they can once again see the pigs, but at the same time also see the spectators opposite looking at the pigs – spectators unaware, or at least pretending to be unaware, that they are being observed. This is the contemporary version of Velásquez’s Las Meninas, and Michel Foucault’s analysis of the classical age of representation.13

What is interesting about this choice for Baudrillard (beyond the fact that he had not forgotten Foucault) is that it offered him a chance to deal with the contemporary but in a sociological context close to the origins of his career. Perhaps he appreciated the strong sense of ironic humor in this pig-sty’s placement beside the Orangerie at Kassel with its royal associations. But while the art was intended to cause humans to reconsider their relations to other animals, Baudrillard must have also enjoyed the suggested comparison between the humans and pigs. What could be better than a pig-sty to emphasize Baudrillard’s idea that “It’s as if art, like history, was recycling its own garbage and looking for its redemption in its own detritus?”14 And doesn’t it follow that these piggish visitors – in addition to the artists – at these large fairs produce [and devour] their own amounts of garbage? Nevertheless, Baudrillard’s commentary points to the continued relevance of his ideas, which are sure to resonate long after his death. This is especially true of his notions about the post-human, whether employed within the topical debate concerning the fine line between humans and other animals as engaged by Höller and Trockel,15 or their implications for more recent trends in “bio art”.16

This passage about a specific work of art also offers a rebuttal to those who express doubts that Baudrillard “exposes himself to contemporary work”.17 Indeed, Baudrillard seems to prefer dealing with “singular works” by artists such as Francis Bacon or Andy Warhol, or even those of Edward Hopper, whom he acknowledges as an influence on his own photographs.18

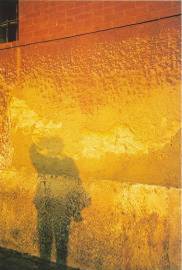

4. Baudrillard. Saint Beuve (1990)

5. Hopper. Morning Sun (1952)19

It should also be remembered that Baudrillard entered into collaborations with other visual artists such as Sophie Calle.20

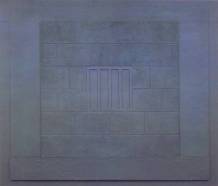

Looking back through Baudrillard’s engagement with the art world, I acknowledge that my first encounter with his ideas came in relation to the Neo-Geo movement of the 1980s, and with artists such as Peter Halley and Barbara Kruger. In his article “The Crisis in Geometry” Halley stressed the importance for him of writers such as Foucault and Baudrillard. Halley’s paintings, with their day-glo acrylic paint, were meant to evoke the artificial as opposed to natural. He described his works

6. Peter Halley. White and Black Cells With Conduit (1986)

as a sort of “‘digital field’ in which are situated ‘cells’ with simulated stucco texture from which flow irradiated ‘conduits’”21 and saw them as being “akin to the simulated space of the video game, of the microchip, and of the office tower” and its “cellular space.” These were clearly meant as a response to passages from Baudrillard’s “Precession of Simulacra”: “The real is produced from miniaturized cells, matrices, and memory banks, models of control – and it can be reproduced an indefinite number of times from these”.22 In this way, Halley, who continues today to repeat his compositions through endless permutations, came to be Baudrillard’s most vocal champion in the U.S.

The result of all this art world attention has been described by Baudrillard’s main advocate in the academic world, Sylvère Lotringer, who noted, “Soon Artforum seized upon Baudrillard’s name and added him to the masthead as contributing editor; a few months later, in Paris, he told me that he had never been asked. He had only vaguely heard about some sudden promotion in a magazine he’d never heard of – but he wasn’t upset. There was a twinkle in his eye. I realized that Baudrillard had finally arrived in America”.23 By 1987, when Baudrillard was invited to deliver the prestigious lecture on American Art and Culture of the Twentieth Century at the Whitney Museum in New York, he was so famous that it sold out months in advance. Shortly thereafter, he was invited by Lotringer to speak at Columbia University, and many artists were in attendance. As Lotringer recalls, “He was asked what he thought about the ‘Simulationist school of painting’ and he simply dismissed the claim. ‘There can’t be any simulationist school,’ he said, ‘because the simulacrum cannot be represented. This is a complete misunderstanding of what I wrote”.24 In his later comments Baudrillard went further: “… the Simulationists of New York, who, by hypostasizing the simulacrum, are only hypostasizing painting itself as a simulacrum, as a machine defeating itself. … This painting has become completely indifferent to itself as painting, as art, as illusion more powerful than the real. It doesn’t believe any longer in its own illusion, and so it falls into the simulation of itself and into derision”.25 When Nicholas Zurbrugg asked him about the “widespread influence” of his “writing upon artists and critics” Baudrillard expressed lack of admiration for “the New York artists who simply reiterate and reproduce familiar modes of simulation.” He argued that:

To assert that ‘We’re in a state of simulation’ becomes meaningless, because at that point one enters a death-like state. The moment you believe that you’re in a state of simulation you’re no longer there. The misunderstanding here is the conversion of a theory like mine into a reference. Whereas there should never be any references.26

Later, Baudrillard offered similar criticism to both the film the Matrix: “There is a misunderstanding, of course, that is the reason why I previously hesitated to talk about The Matrix ….”27 At the same time, however, perhaps Baudrillard’s own photographs are trapped somewhere within this situation. For example, doesn’t his photograph, Venice 1989, engage not with the “real” Venice in Italy, but with Venice Beach, California?

7. Baudrillard. Venice (1989)

Moreover, I wonder if Peter Halley’s work and The New Geometry is worthy of reconsideration after 9/11? Was he really onto some sort of sleeper cells long before we all (after Baudrillard, of course) became totally obsessed with these hidden systems? Do Halley’s prisons call attention to a more pervasive and significant pattern than any of us were ready to acknowledge at the time? Certainly this theme holds a much greater poignancy now that one of the central images of our time

8. Peter Halley. Cinderblock Prison (1990)

9. Abu Ghraib Prison. Prisoner of US Armed Forces being tortured

has been Abu Ghraib man, which Baudrillard discussed in his lucid essay “War Porn”.28 But if Baudrillard became far less than the patron saint Halley had hoped to find, Halley also turned out to be a compromised champion of Baudrillard; he also ended up participating in the Resistance (Anti-Baudrillard) show at White Columns Gallery in 1987. Ironically, Halley’s critics now speak mainly of his formal achievements, the quality of his color, and so forth, at a time when Baudrillard had turned to “form” as one of the irreversible elements of the visual arts. But alas, like Baudrillard, Halley never quite made it to Documenta, which is where we began, and we should start to make our way back there.

Baudrillard has also offered a good deal of fascinating commentary on architecture, and in a couple of key cases, we find his interests there converging with significant insights on another sphere that has become intimately involved with the image: the specter of terrorism. Long before his ideas were taken up by Peter Halley and the New York Simulationists, Baudrillard had taken on the Beaubourg Center in Paris, which, after having been closed down for repairs, is now celebrating its 30th anniversary. He described this structure, which had been erected on the edge of the Marais district, as being like an incinerator, a nuclear power plant, a black hole and/or an oil refinery.29 Baudrillard managed to “blow-up” this most often visited of tourist sites long before it came to be considered a high-value target for terrorists, or at least by the counter terrorists. More recently, in February of 2002, Baudrillard delivered his insightful, if provocative, comments on the World Trade Center (about which he had also written earlier essays). In his “Requiem for the Twin Towers” he wrote: “These architectural monsters, like the Beaubourg Centre, have always exerted an ambiguous fascination, as have the extreme forms of modern technology in general – a contradictory feeling of attraction and repulsion, and hence, somewhere, a secret desire to see them disappear”.30 But perhaps his most memorable phrase is as follows: “The violence of globalization also involves architecture, and hence the violent protest against it also involves the destruction of that architecture. In terms of collective drama, we can say that the horror for the 4,000 victims of dying in those towers was inseparable from the horror of living in them – the horror of living and working in sarcophagi of concrete and steel”.31 Baudrillard argued that “There is an absolute difficulty in speaking of an absolute event. That is to say, in providing an analysis of it that is not an explanation – as I don’t think there is any possible explanation of this event …” even for intellectuals. Instead, he offered what he called the “analogon” which he described as “an analysis which might possibly be as unacceptable as the event, but strikes the … let us say, symbolic imagination in more or less the same way”.32 In this way, he invokes his favored strategy of reversibility, which has been discussed at length by Gerry Coulter. Coulter calls upon the following passage from Baudrillard’s “Simulacra and Simulation” essay to emphasize this point: “‘One must push what is collapsing,’ said Nietzsche. … I am a terrorist and a nihilist in theory as the others are in weapons. Theoretical violence, not truth, is the only resource we have left to us”.33

Indeed, Baudrillard has often been cast in the role of “intellectual terrorist” and he has also spoken of the “(unwittingly) terroristic imagination which dwells in all of us”,34 even if he emphasizes that literal physical acts of terrorism are immoral. For example, in an interview with Nicholas Zurbrugg he said, “I’m a very bad aesthetic analyst! And it’s perhaps for that reason that I often have a more brutal reaction!” When Zurbrugg asked him if he enjoyed being a “theoretical terrorist?” his response was: “Yes, I think it’s a valid position – for the moment, I can’t envisage any other. It’s something of an inheritance from the Situationists, from Bataille, and so on. Even though things have changed and the problems are no longer exactly the same, I feel I’ve inherited something from that position – the savage tone and the subversive mentality. I’m too old to change, so I continue!”35 In the same interview, Baudrillard said “because it is no longer possible to assume a purely critical position. We need to go beyond negative consciousness and negativity, in order to develop a worst-possible-scenario strategy (une stratégie du pire), given that a negative, dialectical strategy is no longer possible today. So one becomes a terrorist”.36

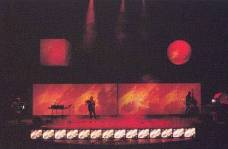

A number of writers and visual artists have adopted this strategy. For example, in a famous quotation from Don DeLillo’s Mao II, his fictional writer, Bill Gray, prophecizes that “in the future artists (writers) will be replaced by terrorists”.37 This idea has been paraphrased by Laurie Anderson in her Stories from the Nerve Bible, a performance piece that commented [as did Baudrillard] on the first Gulf War. In one section of the work, “The Cultural Ambassador,” she describes her experience of working in Israel at the time. She paraphrases DeLillo’s quote about how “terrorists are the only true artists left because they are the only ones capable of really surprising people” and she examines the way in which “the media coverage of the war was

10. Laurie Anderson. Stories from the Nerve Bible

11. Laurie Anderson. Stories from the Nerve Bible

something between grand Opera and the Super Bowl”.38 In some ways, this is a sort of “theory piece” for her “Night in Baghdad” sequence, where she appropriates the narrative from CNN coverage and the reporter’s comments about everything being so “euphoric”, so “beautiful.”

Another artist who comes to mind is Stephen Kurtz, a professor at the State University of Buffalo, and a member of the Critical Art Ensemble. The Ensemble’s contributions were discussed in a New York Times article39 by Randy Kennedy, who described how the group “pushed the art deep into the realm of activism, questioning the activities of the biotechnology industry and even proposing what they call ‘fuzzy biological sabotage’ – such as releasing strange-looking genetically mutated flies into offices and restaurants around biotech-company plants to sow paranoia or releasing rats near fields where genetically altered plants are being tested so that they invade and destroy the test samples.” However, Kurtz’s life took an unexpected turn on May 11, 2004, when, after calling 911 “to report that his wife, Hope, 45, was not breathing” the authorities arrived only to find her dead and to discover something else in a hallway: “a biological lab with an incubator, centrifuge and bacterial cultures growing in petri dishes” and bookshelves that held titles such as The Biology of Doom and Spores, Plagues and History: The Story of Anthrax. Although evidence has shown that there was no foul play in his wife’s death from heart failure, F.B.I. agents began to investigate Kurtz, citing sections of the Biological Weapons Anti-Terrorism Act. He is currently awaiting trail, and a possible twenty years in prison. In the context of Baudrillard’s writings, we realize that Kurtz was invoking a kind of “fatal strategy” by pushing scientific systems to their logical conclusion of collapse – and perhaps even the authorities now realize the danger of this strategy.

12. Stephen Kurtz

In all of these works we find a response to a kind of “aesthetics of terror.” Consider for example, Frank Lentricchia, who claims that DeLillo’s writing “represents a rare achievement in American literature – the perfect weave of novelistic imagination and cultural criticism”, with a “final prospect [that] is both terrifying and beautiful”.40 This latter aspect is one of the most perplexing dilemmas of our time and our aesthetics and critical mechanisms are not well equipped to deal with it. For example, we might consider how these experiences are linked in two examples from the news media: 1) the crash of Cypriot Helios Airlines Flight 422 in Greece – with a press photo (below left) and the “aestheticized” reversed

13 and 14. Crash scene: Cypriot Helios Flight 422

image as it appeared in my local paper – or 2) the orange fireball against blue skies framed by the Manhattan skyline on 9/11 with its Impressionistic use of simultaneous contrast of colors. In his exquisite and incisive essay, The Spirit of Terrorism,

15. 9/11

16. Monet. Impression Sunrise (1973)

Baudrillard spoke of our urgent need to respond to the events of September 11, 2001: “you have to move more slowly – though without allowing yourself to be buried beneath a welter of words, or the gathering clouds of war, and preserving intact the unforgettable incandescence of the images”.41

But the challenge for artists, according to Baudrillard, is that “a work of art no longer has any privilege as a singular object of breaking through this type of circuit, of interrupting the circuit in some sense – because that is what it would amount to, a singular, unique appearance of an object unlike any other”.42 One extreme example of an aspiring English student’s attempt to overcome this would be Seung-Hui Cho’s shootings at Virginia Tech in May of 2007, whose efforts were ultimately described by NBC Evening News as a “multimedia manifesto.”

17. Seung-Hui Cho

In this light, one wonders if DeLillo’s famous statement must be revised to say, “In the future the only true artists will be mass murderers?” In another context, we might wonder whether the failure of the U.S. government’s efforts at “shock and awe” at the beginning of the Iraq “war” suggests the need for a change of direction. Perhaps a better solution than spending so much of our effort (and money) on the “war on terrorism” or on “counter terrorism,” would be to focus instead on the development of an “aesthetics of terror.” If this does not suggest the need for a possible President’s cabinet level position, then surely a university could create an academic chair, or at least form a committee to focus on the “aesthetics of terror” – I can almost hear Baudrillard laughing.

To return briefly to the work by Beuys with which we began, I should note that I had originally considered that his title, might be paraphrased as something like: “Baudrillard, I will personally guide Bin Laden (or Al Qaeda) through Documenta 12.” While this might be somewhat more appropriate to the shock value invoked by Beuys/Peiter, it would have made Baudrillard into a kind of patron saint (a latter day Dürer). But it seemed a bit too dangerous to engage Bin Laden (or Al Queda) in this way at this moment, and who would believe, today, as Beuys did in 1972, that such a visit to an art exhibition might be a therapeutic way of reintroducing these terrorists back into society? It is sad to recognize that we will not have the chance this year of hearing of Baudrillard’s response to this “non-event” in Kassel, but it is certain that it will be impossible to visit Documenta, or to critique the strategies of the artists and curators there, without thinking of Baudrillard and of the strategic challenges his work has posed. In my mind, he will have left a long shadow over the objects that encounter us there.

18. Baudrillard. Punto Final (1997)

About the Author

Dr. Leslie S. Curtis is from the Department of Art History and Humanities, John Carroll University, Ohio, USA.

Endnotes

1 -I wish to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Joseph Tanke for organizing this session of the IAPL and for his insightful commentary on this paper. I would also like to thank Dr. Linda Koch.

2 – Jean Baudrillard. Baudrillard Live: Selected Interviews (Edited by Mike Gane). London: Routledge, 1993:132.

3 – This work is discussed at length in several sources. Joseph Beuys: Just Hit the Mark; Works from the Speck Collection. Exhibition catalogue, London, 10 September to 15 November 2003 and New York, 9 January to 14 February 2004: 14, 70-71, 96, 104-106. London and New York, Gagosian Gallery; Michaela Unterdöfer, I Believe in Dürer (Kunsthalle Nürnberg, 2000): 26. Veit Loers and Pia Witzmann (Editors), Joseph Beuys: documenta-Arbeit (Kassel: Museum Fridericianum, 1993): 114. Peter-Klaus Schuster, “Man as His Own Creator: Dürer and Beuys – or the Affirmation of Creativity,” in Joseph Beuys in Memoriam, Obituaries, Essays, Speeches, Bonn: Inter Nationes, 1986: 21. Paris, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Joseph Beuys, Exhibition catalogue, 30 June to 3 October 1994; organized by the Kunsthaus Zürich, 26 November 1993 to 20 February 1994): 172-173, and 324-325.

4 – Jean Baudrillard, Interview from La Sept (Société d’édition de programme de Television) television programme: “L’objet de l’art à l’âge électronique” (May 8, 1987). The series included interviews with Stuart Hall, Yves Michaud, Jean Baudrillard, and Paul Virilio. This was published in English with a translation by Lucy Forsyth in “The Work of Art in the Electronic Age,” Block (Autumn 1988), 14: 8-10. Reprinted in Mike Gane (Editor), Baudrillard Live: Selected Interviews, London and New York: Routledge, 1993:147.

5 – For example, he refers to Arthur C. Clarke’s fable, “The Nine Billion Names of God,” in “Aesthetic Illusion and Virtual Reality,” Jean Baudrillard. Art and Artefact, Nicholas Zurbrugg (Editor), London, Thousand Oaks, and New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1997: 23.

6 – Jean Baudrillard. “No Nostalgia for Old Aesthetic Values” interview with Genevièvre Breerette, 1996; reprinted in Jean Baudrillard, The Conspiracy of Art; Manifestoes, Interviews, Essays, edited by Sylvère Lotringer, translated by Ames Hodges, Cambridge, Massachussets and London, England: The MIT Press, 2005:61.

7 – Jean Baudrillard. “La Commedia dell’Arte,” Interview with Catherine Francblin, 1996. Reprinted in Jean Baudrillard, The Conspiracy of Art; Manifestoes, Interviews, Essays, edited by Sylvère Lotringer, translated by Ames Hodges. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The MIT Press, 2005:65.

8 – Jean Baudrillard. “Art Between Utopia and Anticipation,” Interview with Ruth Scheps, 1996. Reprinted in Jean Baudrillard, The Conspiracy of Art; Manifestoes, Interviews, Essays, edited by Sylvère Lotringer, translated by Ames Hodges, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The MIT Press, 2005: 56.

9 – “The 50th Venice Biennale marked its closing with a timely conference on “Globalization, Cultural Identity and Contemporary Art.” Organized by the French and German governments, the conference united Biennale curator Francesco Bonami with artists, philosophers, politicians, and economists for a day of debate at the University of Venice.” The author, Jennifer Allen cites the comments of Harry Nutt in the Frankfurter Rundschau: “Bonami described the contemporary curator as a figure who crisscrosses the globe on a worldwide safari, collecting, and inevitably homogenizing, disparate artworks. While artist Michelangelo Pistoletto pleaded for heterodoxy, philosopher Jean Baudrillard cleared the field by claiming that art has lost its ability to establish any relation beyond aesthetics. For his part, philosopher Peter Sloterdijk sees art only in connection to capitalism, with artworks acting as capitalist agents for coming waves of ‘tastelessness.’ Jennifer Allen, in the “International News Digest” Artforum, November 3, 2003: http://artforum.com/news/week=200345

10 – Charlotte Higgins, arts correspondent for The Guardian, announced the event as follows: “The controversial French writer Jean Baudrillard, notorious for his essay “The Gulf War Did Not Take Place” and his trenchant views on the symbolism of the attacks on the World Trade Centre, will make a public appearance in London in the autumn for the first time in six years. The 77-year-old will speak at the Frieze art fair on October 14, in conversation with the literary theorist Sylvère Lotringer. She quoted Amanda Sharp, co-organizer of the fair, as saying: “He is the most important intellectual working today: an icon. If you ask any young artist who the most important writer on sociology or philosophy is, they will tell you Baudrillard. He is very au courant, from what he says about politics to what’s happening in art practice.” The Guardian, Thursday August 3, 2006. This was also announced in the Saatchi blog: “The theorist last spoke in London in 2000 and has never previously appeared in the context of an art fair. ‘Art Beyond Art,’ Baudrillard in conversation with the philosopher and literary theorist Sylvère Lotringer founder of Semiotext(e), will take place on Saturday 14 October.” , posted on August 6, 2006. Due to the illness which would claim his life in 2007 Baudrillard was unable to attend.

11 – This slight or oversight was noted by Corinna Ghaznavi and Felix Stalder in “Baudrillard: Contemporary Art is Worthless,” Lola, a Toronto-based independent art magazine (February 1998). However, judging from their commentary it is not clear that they were not exactly sympathetic with Baudrillard: “Is he still being taken seriously? A notable exclusion from Catherine David’s “Documenta” book is Jean Baudrillard, although almost all influential theorists since 1945 have been included. Was this in recognition of the fact that there is no substance to his discourse anymore? Was it the exclusion from the French intellectual circle that moved him to such a hefty reaction? “The Precession of the Simulacra” remains impressive, if somewhat exaggerated (did it really take him that long to discover the remote control?).” Elsewhere, Sylvère Lotringer has countered their commentary: “It didn’t help much, of course, that they relied on a faulty translation, or simply misread his argument. Baudrillard’s claim that anyone criticizing contemporary art (as he does) is being dismissed as a ‘reactionary…… even fascist mode of thinking’ is turned around and presented as an attack on art.” See Lotringer, “The Piracy of Art,” International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Volume 2, Number 2, July 2005. Lotringer’s article was the introduction to Jean Baudrillard, The Conspiracy of Art, New York: MIT, 2005.

12 – Catherine David. “Introduction,” translated by Brian Holmes, Short Guide, Documenta X Germany: Cantz Verlag, 1997: 7.

13 – Jean Baudrillard. Impossible Exchange, translated by Chris Turner, London and New York: Verso 2001:107.

14 – Jean Baudrillard. “Objects, Images, and the Possibilities of Aesthetic Illusion,” in Jean Baudrillard, Art and Artefact, edited by Nicholas Zurbrugg, London, Thousand Oaks, and New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1997: 8.

15 – Baudrillard liked to pepper his writings about art with references to relations between humans and non-human animals. See for example his reference to Elias Canetti in “Objects, Images, and the Possibilities of Aesthetic Illusion,” in Jean Baudrillard, Art and Artefact, edited by Nicholas Zurbrugg, London, Thousand Oaks, and New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1997: 12. He also commented more directly and at length on these issues in “The Animals: Territory and Metamorphoses” in Simulacra and Simulation, translated by Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994:129-142.

16 – For more of a discussion on bio art, see the section on Kurtz and the Critical Art Ensemble below. One also looks forward to a consideration of how the ideas of this trained sociologist related to the tendency towards sociological approaches in art history – even if one of the areas where this was especially predominant was in the 19th century, while Baudrillard more often talked about contemporary art (or modernist art after the 19th century).

17 – Daniel Birnbaum, “Backstage Presence: Interview with Suzanne Pagé, director of the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris” Artforum, February 1998:78. In response to Birnbaum’s question “Recently there have been a number of fierce attacks on contemporary art by French writers such as Jean Clair and Jean Baudrillard. How has that affected your work in the museum?” she responded: “It’s dangerous, because it has a real impact on a very anxious part of the population. Clair and Baudrillard are obviously respectable in a certain way, but I doubt that they expose themselves to contemporary work, and their defensive discourse can seem to be a kind of armor to protect themselves from the certainty of the world. I also think that there is a problem of power, and that certain intellectuals can be jealous of artists because art can’t really be justified – no discourse can legitimate it. The artists can’t be grasped.”

18 – Graz, Austria: Neue Galerie Graz am Landesmuseum Joanneum, Jean Baudrillard: Photographies, 1985-1998 (exhibition catalogue, Graz 9 January to 14 February 1999 with essays by Peter Weibel and Christa Steinle). Also see Gerry Coulter and Kelly Reid, “The Baudrillardian Photograph as Theory: Making the World a Little More Unintelligible and Enigmatic,” International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Volume 4, Number 1, January 2007.

19 – Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio, USA.

20 – Sophie Calle and Jean Baudrillard. Suite Vénitienne/Please Follow Me. Paris: Editions de l’Etoile, 1983. He also collaborated with her on Unfinished (2003). See Paris, Musée national d’art moderne, M’as-tu vue (Exhibition catalogue, 19 November 2003 to15 March 2004: 24-25 and 413-430. See also, Rex Butler, “Baudrillard’s Light Writing or Photographic Thought,” International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Volume 2, Number 1, January 2005.

21 – Peter Halley. “The Crisis in Geometry,” Arts Magazine, 58; 10, June 1984:115.

22 – Ibid.:115.

23 – Jean Baudrillard. “The Precession of Simulacra,” in Simulacra and Simulation (c 1981), translated by Sheila Faria Glaser, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994: 1-42.

24 – Sylvére Lotringer. “Better Than Life, My 80’s” Artforum, 41; 8, April 2003:194-197 and 252-253.

25 – Ibid. As a result, Halley was soon to become the whipping boy for critics who held him up as the most notable example of an artist who had overindulged in theory.

26 – “… the Simulationists of New York who, by hypostasizing the simulacrum, are only hypostasizing painting itself as a simulacrum, as a machine defeating itself. In many cases (Bad Painting, New Painting, installations and performances) painting denies itself, parodies itself, rejects itself. Plasticized, vitrified frozen excrement, or garbage. It does not even justify a glance. It doesn’t look at you, and so in turn you don’t need to look at it; it is no longer your concern. This painting has become completely indifferent to itself as painting, as art, as illusion more powerful than the real. It doesn’t believe any longer in its own illusion, and so it falls into the simulation of itself and into derision.” Jean Baudrillard, “Objects, Images, and the Possibilities of Aesthetic Illusion,” in Art and Artefact, edited by Nicholas Zurbrugg, London, Thousand Oaks, and New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1997:10.

27 – Jean Baudrillard. “Fractal Theory,” interview with Nicholas Zurbrugg, in Baudrillard Live: Selected Interviews. Edited by Mike Gane, London: Routledge, 1993:166.

28 – “What we have here is essentially the same misunderstanding as with the simulationist artists in New York in the 1980s. These people take the hypothesis of the virtual as a fact and carry it over to visible fantasms. But the primary characteristic of this universe lies precisely in the inability to use categories of the real to speak about it.” Jean Baudrillard, interviewed by Aude Lancelin, Le Nouvel Observateur, July 23, 2003). I have not been able to find who translated this quote which has been posted on a number of internet sites cf. http://daily.greencine.com/archives/003365.html (link no longer active 2019)

29 – Even the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has recognized the extreme relevance of a film like The Lives of Others and its analysis of the society of surveillance which surrounds us.

30 – Jean Baudrillard. “The Beaubourg Effect: Implosion and Deterrence,” in Simulacra and Simulation, translated by Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994: 61-73. In terms of deterrence, Baudrillard wrote: “All around, the neighborhood is nothing but a protective zone – remodeling, disinfection, a snobbish and hygienic design – but above all in a figurative sense: it is a machine for making emptiness. It is a bit like the real danger nuclear power stations pose: not lack of security, pollution, explosion, but a system of maximum security that radiates around them, the protective zone of control and deterrence that extends, slowly but surely, over the territory – a technical, ecological, economic, geopolitical glacis”.

31 – Jean Baudrillard. The Spirit of Terrorism and Requiem for the Twin Towers, translated by Chris Turner, London and New York: Verso, 2002: 46.

32 – Ibid.:45.

33 – Ibid.:41 note 1.

34 – Gerry Coulter. “Reversibility: Baudrillard’s ‘One Great Thought’” International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Volume 1, Number 2, July 2004. Baudrillard as quoted from Simulacra and Simulation (c.1981). Trans. Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1994:153: “One must push at the insane consumption of energy in order to exterminate its concept. One must push at maximal repression in order to exterminate its concept. … ‘One must push what is collapsing,’ said Nietzsche. …I am a terrorist and a nihilist in theory as the others are in weapons. Theoretical violence, not truth, is the only resource we have left to us.” In thinking about how art writers (historians, critics, theorists) have responded to Baudrillard, it seems to often be forgotten the extent to which, as Coulter emphasizes, that Baudrillard used “theory as challenge” and this may explain why artists themselves have been attracted to Baudrillard’s ideas because they are also frequently seeking to challenge with their art.

35 – Jean Baudrillard. The Spirit of Terrorism and Requiem for the Twin Towers, translated by Chris Turner, London and New York: Verso, 2002:5.

36 – Mike Gane (Editor). Baudrillard Live: Selected Interviews. Edited by Mike Gane, London: Routledge, 1993:168.

37 – Don DeLillo. Mao II. New York: Viking, 1991.

38 – This also reminds me of Don DeLillo’s musings on the parallels between thermonuclear war and football in his early novel, End Zone, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1972.

39 – Randy Kennedy. “The Artists in the Hazmat Suits,” New York Times, July 3, 2005.

40 – Frank Lentricchia. as quoted by Vince Passaro, “Dangerous Don DeLillo,” Thomas DePietro, (Editor). Conversations with Don DeLillo, Jackson, Mississippi: University of Mississippi Press, 2005: 83.

41 – Jean Baudrillard. The Spirit of Terrorism and Requiem for the Twin Towers, translated by Chris Turner, London and New York: Verso, 2002:4.

42 – Jean Baudrillard. “The Work of Art in the Electronic Age,” in Mike Gane, ed., Baudrillard Live: Selected Interviews. Edited by Mike Gane, London: Routledge, 1993:147.