ISSN: 1705-6411

Volume 9, Number 2 (July 2012)

Author: Dr. Gerry Coulter

The only rule is that there are no rules. Anything is possible… it’s all about taking risks… deliberate risks (Helen Frankenthaler, Interview with Charlie Rose, 1993)

Helen Frankenthaler in 1957 with Mountains and Sea (1952)

Frankenthaler brought to mid 20th century abstraction a lyrical approach and a new method of allowing the paint to “stain” the unprimed canvas. Her pouring approach, which she devised while watching Pollack dance and drip over his canvases laid out on the floor, further released colour from the limitations of gesture. Prior to Frankenthaler, abstraction had mainly consisted of a “skin” of paint applied over a primed canvas. Her method called upon the paint to become one with the canvas. It was a significant methodological development which influenced a generation of “post painterly abstractionists” (Clement Greenberg’s term) or Colour Field Painters as the official art world prefers to frame them today.

Frankenthaler. Mountains and Sea (detail, 1952)

“Lyrical” is a synonym for words such as poetic, emotional, inspired, and romantic. In the 1950s it was also frequently associated with “feminine” as was Frankenthaler’s approach. Admittedly, it is difficult at first glance, not to see something of a ‘feminine’ hand in her work especially given the hard edged abstractions of the likes of Clyfford Still at the end of the 1940s. When we look more closely and think more about abstraction as a series of movements we can understand that Frankenthaler quite rightly rejected efforts to “feminize” her method. She was of course very well aware that “feminine” would be used to mainly denigrate her work and to cast her as a less serious artist. Later, especially with Rothko and Olitski, we see a similar delicate lyricism and balanced poetry which were not labelled ‘feminine’ approaches. If Frankenthaler made an especially gendered art then what are we to say of the work of Olitski – a male abstractionist who’s work is often be confused with that of Frankenthaler?

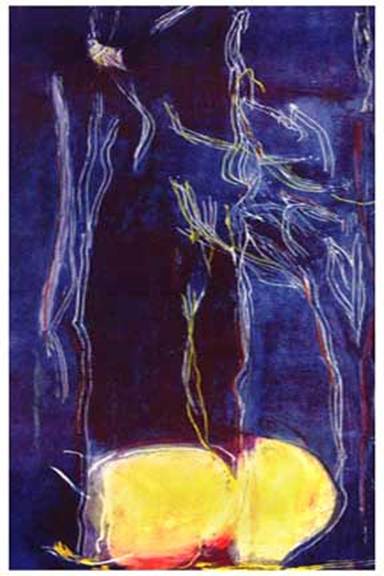

Frankenthaler. All About Blue (1994)

Frankenthaler rejected all efforts, feminist and otherwise, to make hers into a specific “woman’s art”. As she told John Gruen for his book The Party’s Over Now (1972): “I don’t resent being a female painter. I don’t exploit it. I paint.” But it was the mid twentieth century and she was a woman and the effort to label was an almost unavoidable fact given the politicization of sex and gender that enveloped the culture in which she thrived. Before long she came under criticism from mid twentieth century feminists for not embracing the women’s movement but Frankenthaler was a very a-political operator. The criticism of women such as Frankenthaler by feminism can only be read as ironic [of the not quite pathetic variety] given the forces already aligned against a woman artist in her time.

Frankenthaler. Robinson’s Wrap (1974)

Frankenthaler was told that she was too poetic (!) while abstractionists like Rothko and Olitski [and others] were praised for their poetry and lyricism. Frankenthaler also offended those who preferred their artists poor and struggling. She was Park avenue born, the daughter of a New York State Supreme Court Justice, and never experienced the kind of economic pressure that forces young artists to sell work. Fresh out of art school she entered into what turned out to be a five year relationship with the leading art critic of the day, Clement Greenberg, who probably propelled her into the public spotlight sooner than she would have achieved on her own. No one today doubts she would have arrived. Frankenthaler was severely rebuked for her relationship with Greenberg as she was for her marriage to Robert Motherwell (1958-1971) with whom she had two daughters. Interestingly, Motherwell was not subjected to the same criticism for marrying an artist. Frankenthaler simply persevered and ignored her otherness for the trap her critics made it into:

Being a female artist was almost unique and at the same time it was, for me, very little of an issue. I had something to say in terms of painting and went about doing it. What has made it work, and what has made certain paintings succeed, or not, has to do with my being a painter and a thinking, feeling, person more than my sex, colour, height, or origin (Interview with Charlie Rose, 1993).

Greenberg also brought her face to face with Pollock in his studio and all the leading abstractionists of the early 1950s. Indeed, it was the meeting with Pollock that allowed her to devise her staining method as a way to get past some of the things frustrating him about painting. Among young artists she in turn influenced were Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis. As Noland said: “We were interested in Pollock but could gain no lead from him – he was too personal. Frankenthaler showed us a way to think about and use colour”. While colour is never entirely free of gesture Frankenthaler’s pouring method [often using sponges to control flows and pooling of paint] did release colour further from gesture than had previously been achieved.

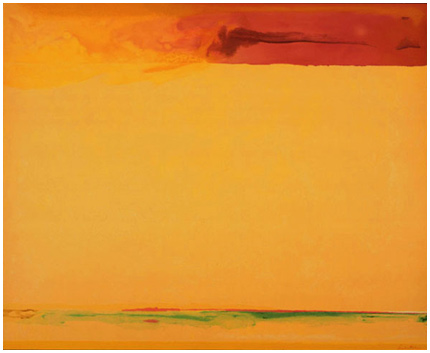

Frankenthaler. Southern Exposure (2005)

She had, from an early age, a deep knowledge of the history of art [something she could converse about with Pollock in his studio] and in her relationship with Greenberg. It is difficult to say which criticism of Frankenthaler was the most banal. My vote is for those who claimed that her work lacked intellectual rigour when in fact she was painting the language of poststructuralism before Derrida or Barthes had learned to speak it. As time passed she became a thoughtful and highly articulate analyst of the poststructural nature of abstraction and the problem of art generally.

I think today, “beautiful” – which is always a tricky word – now has become an incendiary word because in so many ways today beauty is obsolete and not the main concern of art. You can’t prove beauty, it is there as a fact and you know it, and you can feel it, and it’s real, but you can’t say to somebody “this has it”. I might be able to say it and others might recognize it – it gives no specific message other than itself, which in turn should be able to move you into some sort of truth and insight and some sort of beyond… (Frankenthaler, Interview with Charlie Rose, April 12, 1993).

Like all good abstractionists Frankenthaler struggled to find ways of showing what she felt yet could not articulate in words. Of late she has gotten some due for being among the most significant “woman” artists of the twentieth century. I wonder when she will get full credit for the pivotal role she once played in the future of abstraction at the middle of the twentieth century? Post-painterly abstraction would have arrived without her. We should not, however, overlook the fact that it was through her insight that it arrived when it did. The entire history of post-painterly colour field painting remains in her debt.

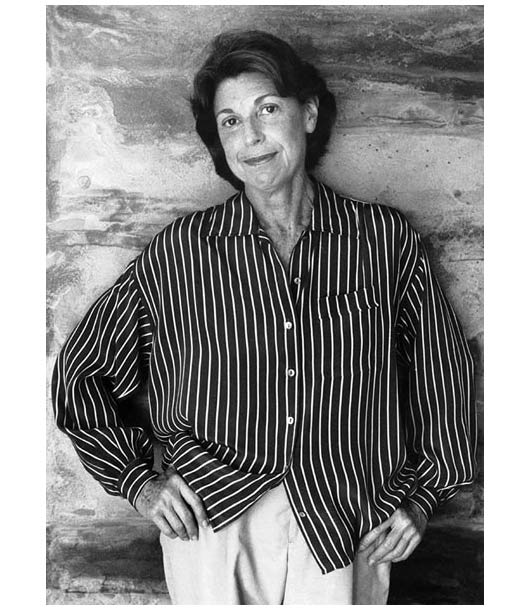

Helen Frankenthaler December 12, 1928 – December 27, 2011

“One is safe if one is still able to risk” (Frankenthaler quoted in New York Times Interview, April 27, 2003)

This remembrance is also dedicated to Dr. Melissa Clark-Jones (New York) [Professor Emeritus, Bishop’s University, Sherbrooke, Quebec].

About the Author

Gerry Coulter is the founder of IJBS.