ISSN: 1705-6411

Volume 3, Number 1 (January 2006)

Author: Kubilay Akman1

I. Introduction

The French performance artist Orlan has risen to an extraordinary position in the contemporary art world. Her motto: “art is a dirty job, but someone has to do it” is given incredible meaning in the surgeries she has carried out on her body to make art. In these artistic performances or “Carnal Art,” she transforms her body and her face in an enactment of a critique of the beauty concept which she feels is embedded in male power and its construction of female-subjects in modern Western societies. In order to better understand Orlan’s artistic philosophy and her artistic production I wish to discuss concepts from both the Western and the Eastern intellectual worlds.

This paper functions as a series of interconnected probes into the work of a Western artist (Orlan), a Western philosopher (Baudrillard) and an Eastern concept (suret).2 Examining Orlan’s art takes me into a discussion of two central concepts in Baudrillard’s thought: seduction and simulation. At first glance we may see Orlan’s art as an example of exactly the kinds of excesses we would expect from the merger of flesh and technology in contemporary society. However, as Nicholas Zurbrugg has argued, some contemporary artists (he refers to Stelarc but it is also true of Orlan), use technology to “reinforce the impact of installation art and performance art exploring and manifesting individual identity”.3 I also wish to point to the usefulness of the concept “suret” in deepening our probe into correspondences between Orlan’s art and Baudrillard’s thought. In the end we find that these probes help us to take tentative steps toward new understandings of old questions once raised by Walter Benjamin.

II. Surgery For An Individual Aesthetic Conception

II. Surgery For An Individual Aesthetic Conception

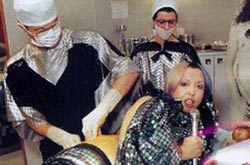

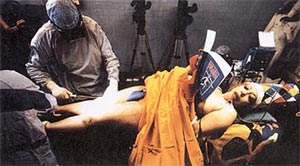

Orlan’s deconstructions of the “beauty concept” are made at the time when many women are turning to aesthetic surgery to move closer to standardized beauty as defined by popular culture. Orlan’s surgery’s have also been understood as art by important voices in the art world for several years. The critical target of her Carnal Art, according to Rose is “the hypocrisy of the way society has traditionally split the female image into Madonna and whore”.4 Rose says that Orlan, whatever the shock value of her art, is a genuine artist, deadly serious in her elaborately calculated performances which take place in “the theater of operation”. What is to stop us from understanding Orlan’s actions as pathological behaviour or simply as “non-art”? Rose argues that there are two essential criteria (intentionality and transformation) which distinguish art from non-art and that both are present in Orlan’s Carnal Art. According to this view, Orlan’s confrontational works are aesthetic actions which force us to reconsider the boundary that separates “normality” from madness, and art from non-art.5 In Orlan’s case, the operating room is her “studio” and her body is not only the medium and material she uses for her work, it is also her work itself and a metaphor of resistance against the stereotypes of aesthetic authority.

Orlan challenges both the notion that the body is unchangeable and the idea that any changes must conform to the standardized style. Orlan claims: “I am a woman to woman transsexual act” but her surgical transformations are far from a sex change operation as they are not permanent. Yet, her efforts may be viewed as a contribution to postmodern feminist theories of identity as she enacts the representation of the celebration of identity as fragmented, multiple and fluctuating. For Orlan, plastic surgery, used outside of the context of popular culture, is a way for her to maintain control of her body. Her project could be considered as an example of a feminist utopia where the utopia is built on the body.6

Orlan challenges both the notion that the body is unchangeable and the idea that any changes must conform to the standardized style. Orlan claims: “I am a woman to woman transsexual act” but her surgical transformations are far from a sex change operation as they are not permanent. Yet, her efforts may be viewed as a contribution to postmodern feminist theories of identity as she enacts the representation of the celebration of identity as fragmented, multiple and fluctuating. For Orlan, plastic surgery, used outside of the context of popular culture, is a way for her to maintain control of her body. Her project could be considered as an example of a feminist utopia where the utopia is built on the body.6

Orlan’s decision to turn surgery into art followed an operation for an extra uterine pregnancy under a local anesthetic where she played both roles of observer and patient. Her present operation/performances are directed by the artist and involve music, poetry and dance. Videos of the surgeries are for sale in the art market as are samples of her flesh and blood drained off during the “body sculpting” process. In the “theatre of operation” members of an audience may also play a role as interactive participants. The role of the audience is an uneasy one as the surgeons insert needles into Orlan’s skin, slice open her lips, or may sever an ear from the rest of her face while Orlan remains silent. Importantly, what Orlan is doing, and what may make the audience so uneasy, is her effort to embody the objectification of the so-called “subject” in a very real way – transcending the border between subject and object. It might even be read as an important contribution to an old problem in Western philosophy – one remembers Goethe: “All theory… is gray!”7

III. Body: Object of Salvation

The soul has been the location of salvation for both religious and secular ideologies. Today, as Baudrillard reminds us, the body (specifically the female body of fashion, advertisements, and mass culture) becomes the object of salvation through hygienic, therapeutic and dietary obsessions.8 In contemporary societies a kind of discourse predominates where the body has manifested its independence from the soul. Baudrillard argues that contemporary structures of “production/ consumption” encourage the subject into a “dual practice, linked to a split (but profoundly interdependent) representation of his/her own body: representation of the body as capital and as fetish (or consumer object)”.9 Rather than being denied, the body becomes the location of deliberate economic and psychic investment. As such, beauty is now an absolute, the religious imperative of capitalism:

Being beautiful is no longer an effect of nature or a supplement to moral qualities. It is the basic, imperative quality of those who take the same care of their faces and figures as they do of their souls. It is a sign, at the level of the body, that one is a member of the elect, just as success is such a sign in business. And, indeed, in their respective magazines, beauty and success are accorded the same mystical foundation: for women, it is sensitivity, exploring and evoking ‘from the inside’ all the parts of the body; for the entrepreneur, it is the adequate intuition of all the possibilities of the market. A sign of election and salvation: the Protestant ethic is not far away here. And it is true that beauty is such an absolute imperative only because it is a form of capital.10

Within the system the mass media idealize a standardized conception of beauty through advertisements and programmatic content. The image of fashion models haunts the self image of women. Every woman participates in this game at least to some extent and it is the mainstay of the of the multi-billion dollar cosmetic, dietary, and hygiene industries. For some the role of the fashion model is to attempt to create a new female version of perfection for all to desire. According to Baudrillard’s thought however:

…the fashion model’s body is no longer an object of desire, but a functional object, a forum of signs in which fashion and the erotic are mingled. It is no longer a synthesis of gestures, even if fashion photography puts all its artistry into re-creating gesture and naturalness by a process of simulation. It is no longer strictly speaking, a body, but a shape.11

Faced with the popularity of the mediated beauty concept, feminists experience great difficulty articulating alternative models of beauty. Some people have even tried to change the rules of the game and give sovereignty back to the soul, but Orlan prefers to play the game by its own rules. If the media society defines salvation in terms of the body, and understands alternatives only in the body, Orlan opens a discussion in the body as well. For Orlan, her surgeries – her performances – her Carnal Art, are an innovative communication strategy. If it is the language of the body that must today dominate, then she will use her body to communicate. Orlan deploys the same kinds of surgical operations the aesthetic surgeons do on women seeking the ideal, but with the goal of creating very different outcomes. Orlan is of course prohibited from communicating with the majority of women as the channels of power allow her to access only a minority. Given her choice of artistic venues and formats, one wonders though if Orlan really wants to communicate widely with other women – is she looking for social or individual salvation? She seems to have achieved an individual salvation in many respects and in the end, this may be the only kind achievable for her. It remains uncertain if she is advocating her art as something for the wider populace to emulate.

Faced with the popularity of the mediated beauty concept, feminists experience great difficulty articulating alternative models of beauty. Some people have even tried to change the rules of the game and give sovereignty back to the soul, but Orlan prefers to play the game by its own rules. If the media society defines salvation in terms of the body, and understands alternatives only in the body, Orlan opens a discussion in the body as well. For Orlan, her surgeries – her performances – her Carnal Art, are an innovative communication strategy. If it is the language of the body that must today dominate, then she will use her body to communicate. Orlan deploys the same kinds of surgical operations the aesthetic surgeons do on women seeking the ideal, but with the goal of creating very different outcomes. Orlan is of course prohibited from communicating with the majority of women as the channels of power allow her to access only a minority. Given her choice of artistic venues and formats, one wonders though if Orlan really wants to communicate widely with other women – is she looking for social or individual salvation? She seems to have achieved an individual salvation in many respects and in the end, this may be the only kind achievable for her. It remains uncertain if she is advocating her art as something for the wider populace to emulate.

IV. Orlan’s Seduction

Everyone seduces and is seduced. Orlan seduces the media, contemporary art audiences, some art historians, some feminists, curators, sociologists and social scientists. She may well be one of the most seductive women of the late 20th Century! It is unlikely however, that images of her body in the theatre of operation will be pinned up beside those of Marilyn Monroe. Many women use their appearance in a strategy of seduction. Seduction has long been the source of woman’s power in social relations and a “mastery over the symbolic universe”.12 Baudrillard reminds us that it is seduction which prevents women from truly being dominated. Masculine power comes from production:

All that is produced, be it the production of woman as female, falls within the register of masculine power. The only and irresistible, power of femininity is the inverse power of seduction. In itself it is null, seduction has no power of its own, only that of annulling the power of production. But it always annuls the latter.13

The common understanding of seduction in modern society is that for a woman to seduce a man she would first transform her external appearance. Orlan goes beyond external appearances to demonstrate that all parts of the body can be external and subject for transformation. She seduces us with her lung, liver, and intestines as well as her external appearance within older meanings of the word. Orlan seeks to deconstruct political discourses involved in established meaning based discourses on the body, replacing them with a primacy of vision. This is once again reminiscent of Baudrillard:

What truly displaces discourse, ‘seduces’ it in the literal sense, and renders it seductive, is its very appearance, its inflections, its nuances, the circulation (whether allegory and senseless, or ritualized and meticulous) of signs at its surface. It is this that effaces meaning and is seductive, while a discourse’s meaning has never seduced anyone.14

Seduction is always a game with traps and one of deception which lies in wait for us and allows us to confuse it with reality. This has potentially a great power.15

In the world of hyper-reality, we are all, says Baudrillard, transsexuals. We have lost sexuality by overproducing it. This rests well within Baudrillard’s overall evaluation of society as “trans” (transeconomic, transpolitical, etc.), and leads us to another correspondence between Baudrillard’s thought and Orlan’s art. In Orlan’s understanding her art is that of a woman performing a transsexual act with herself. For me, her art is a transaesthetic expression as well in that she performs, in a highly individual style, what Baudrillard says of our entire society. Orlan may seem an extreme case, but have we not learned from Baudrillard many times that it is by looking at extreme cases we learn much about our society?

Orlan has transcended the borders of woman and even the borders of sexuality in Carnal Art. This is another way to be transsexual, different than the psychosexual and symbolic meaning of the word. However the result is that she is in a transsexual position where she meets others and here she completes the separation between notions and practices. Orlan’s artistic self-reflection process is thus opened as have been her internal organs. Her artistic practice mixes the techniques used in actual transsexual operations with the concept of transsexuality.

V. Mocking Parodies

Orlan’s artistic production can be understood as a parody of the practice of the ancient Greek artist Zeuxis who chose the best parts of different women and combined them to obtain the ideal image of woman (as often is the case with the digitalized images of models we see in magazines today). Orlan also selects different features from famous Renaissance and post-Renaissance representations of “ideal” beauty and has these applied to her body. Using computer-generated images, and the skill of surgeons, she combines the nose of a famous sculpture of Diana, the mouth of Boucher’s Europa, the chin of Botticelli’s Venus, the eyes of Gerome’s Psyche and the forehead of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. The operating rooms are decorated with enlarged reproductions of the related details of these works. In her deconstruction of Western art history she selects these female prototypes for reasons involving history and mythology:

She chose Diana because the goddess was an aggressive adventuress and did not submit to men; Psyche because of her need for love and spiritual beauty; Europa because she looked to another continent, permitting herself to be carried away into an unknown future. Venus is part of the Orlan myth because of her connection to fertility and creativity, and the Mona Lisa because of her androgyny – the legend being that the painting actually represents a man, perhaps Leonardo himself.16

Orlan says that, “after mixing my own image with these images, I reworked the whole as any painter does, until the final portrait emerged and it was possible to stop and sign it”.17

Orlan is not naive in her enterprise. Her use of Western art history as parody and her simultaneous refusal of this art historical inheritance fuses humor with horror. Her work is paradoxical as it belongs to the Western art tradition while displaying antipathy towards it. A similar tendency can be witnessed in the works of American photographer Joel Peter Witkin18 and modern American author Chuck Palahniuk19 who struggle against the main principles of Western culture. It is very interesting that one of Palahniuk’s novels, Invisible Monsters, is about the transformation and mutilation of body and face, surgery operations, and related identity problems.20

Orlan’s art could be analyzed with its similarities to the other performance artists like Bob Flanagan21 , Yves Klein22 , Chris Burden23 and Marina Abramovic24 . However, two important points separate her from the others. First, among these is pain. Orlan does not suffer from pain due to the use of anesthesia while these other performance artists feel pain – and in masochistic terms we can say they desire it. The second difference is that that Orlan’s art is a profoundly imagined and calculated totality. She builds her work of art through her whole life. This is work that is not spontaneous or aggressive – to the contrary, it is a work of art that is very consciously organized after detailed planning. When it is finished she does not walk away from it, she wears it and lives it.

Even without pain art is a matter of life and death for Orlan despite her tranquility about the operations. There is always the element of risk as she is face to face the possibility of infection and death. Orlan sacrifices and spends her body day to day for art and the body is not an endless resource. Perhaps this is an intimate kind of postmodern potlatch.25 What is spent and gifted is the body and what is gained is the artistic pleasure. At the same time as Orlan presents her Carnal Art, she is reflecting upon the new/revolutionary level that art has attained. While practicing her theory of Carnal Art, she undertakes the mission of representation of these practices.

In her Carnal Art Manifesto, Orlan ironically states that Carnal Art is a self-portrait in the classical sense, yet realized through the technology of its time. It is an inscription in flesh lying between figuration and disfiguration that our age now makes possible. According to Orlan the body should become a “modified ready-made”. Here the pain is not a means of redemption or purification as in other Body Art. There is not a wish to achieve a final “plastic” result, but rather Carnal Art seeks to modify the body and engage in public debate including a challenge to the Christian tradition and its body-politics. Orlan transforms her body into language and with her own words she is reversing the Christian principle of “the word made flesh”, as in her work, the flesh is made word. Only her voice remains unchanged. She judges the famous “you shall give birth in pain” as anachronistic nonsense. In her Carnal Art performances local anesthetics and multiple analgesics defeat pain. In her words: “long live morphine!”

When the artist watches her body cut open, all the way down to her entrails, she reaches a new version of the “mirror stage”. Carnal Art’s purpose is to problematize the status of the body and the ethical questions posed by it. In the most general sense, this critique also applies to the male body, although Orlan’s interest is confined, in her work, to her own female body:

Carnal Art loves the baroque and parody; the grotesque, and the other such styles that have been left behind, because Art opposes the social pressures that are exerted upon both human body and the corpus of art. Carnal art is anti-formalist and anti-conformist.26

Following Orlan’s Manifesto we might add that Carnal Art could be considered as an anti-authoritarian political discourse because it rejects authority, domination, and codes of the power as a kind of bio-opposition. In the final analysis, Orlan’s body is reformed and transformed depending on her own choosing, not by simply following traditions or fashion. This is perhaps one of the higher levels of human freedom one can attain in relation to one’s own body (an ironic goal in relation to twentieth century feminism’s struggles for women’s control of their own bodies). Carnal Art could never become a social liberation project as it operates as a guide to personal freedom, self-control, emancipation and liberation of only the artist. However, it could be connected to the social politics in some aspects through a critical version of feminist theory and movement. In an age when political reason has become highly totalitarian, the discourse of Carnal Art has many anti-totalitarian commonalties with the thought of contemporary theorists including Lyotard, Deleuze, Foucault and Baudrillard.

VI. Welcome to the Desert of Suret?

When we examine the “Carnal Art” of Orlan, the “theater of operation” or “body sculpting” we frequently encounter words such as: face, image, appearance, view, reflection, form, feature, way, style, copy, text, picture, photography, etc. We discuss and consider her performance art and the recreation her body through these words. For Western scholars it may come as a surprise to learn that there is an Eastern word that covers all the meanings of these words: “suret”. In Turkish dictionaries we see that this word originally comes from Arabic and has the meanings of appearance, view, form, shape, face, feature, way, style, copy of a picture or a text, a duplicate, the apparent aspect of existence in Islamic philosophy, and in some contexts picture/painting and photography.27 This word which is less often used in Turkish, has no single equivalent in the English language.

We can agree that Orlan’s transformations involve her face, which changes continually, before everything. The face is usually understood as identical to identity generally, and changeable (slowly), only by time. For Orlan the face changes quickly – her work is a text in inter-textual relations with other texts from history and the modern world. She decides her appearance and view – these are the basic elements of her aesthetic discourse, through her own way and style. On the one hand she copies paintings from art history while producing her work, on the other she reproduces or duplicates herself through photographs and videos. Suret, in the context of Orlan’s work, is an important explanatory concept – the kind of concept her work demands.

Walter Benjamin discussed the transformation of artwork in the age of mechanical reproduction. Today it seems we are in the age of hyper-mechanical organic reproduction. The artist reproduces her art in an organic way while using both mechanical and digital reproduction techniques. This is however, a reproduction that eliminates the difference between the original and the copy and again we return to Baudrillard. The power of the concept of suret comes from the fact that it is located in a sphere where Baudrillard’s concepts of simulation and seduction are also to be found – but it goes further for those of us in the East. Suret is a state of simulation enhanced with a seductive dimension. Perhaps it is even more fascinating with its Eastern, mystical seductiveness. I think now of the tale referenced by Baudrillard in explaining his concept of seduction: suret too is like the redness on the edge of the tail of fox.28 Another meaning of suret, according to Islamic philosophy, is the apparent, perceivable aspect of existence. In this view, everything is suret and we can never be cognizant of its precise essence. On the surface, to some, it may seem like an Oriental version of the “Matrix philosophy”. But the problem is more complicated.

VII. An Historical Meeting: Simulation and Suret

Suret, given its meaning in Turkish, comes quite close to simulation, but it is quite possible that these two words have never before met. This is an historical meeting as one concept comes from history, and the other one is very explanatory for the extreme social situations of our age; one of them is purely Eastern while the other has been defined in the West; one of them includes certain religious meanings while the other belongs to a post-religious (or transreligious) age. Despite the different contexts both point to similar hyper-real conditions – the very conditions under which Orlan’s artistic discourse takes place.

Baudrillard reminds us that simulation is opposed to representation. According to the latter the sign and the real are equivalent. However simulation starts from the radical negation of the sign as value, from the sign as reversion and death sentence of every reference and envelops the edifice of representation as itself a simulacrum:

This would be the successive phases of the image: it is the reflection of a basic reality. It masks and perverts a basic reality. It masks the absence of a basic reality. It bears no relation to any reality whatever: it is its own pure simulacrum.29

Today the simulation process in societies reaches its last phase. The problem is not the reflection, perversion or masking of any reality. The simulacra have no relation with an outside reality – it is the contemporary reality itself. There is no longer separation between copy and original. Social phenomena are becoming more and more every day like the reproduction of a digital file.

In many aspects suret also indicates the termination of differences between original and copy, reality and image, essence and appearance. According to its philosophical meanings everything perceived is suret. And it includes the sense of duplicates or copies like clones. Orlan’s Carnal Art can be understood as the place of correspondence of these two concepts. While producing her surets she is immersed in a simulation process. Which face is Orlan’s and which one is the copy? Her simulacra have lost their “connections” for a some time now.

Despite all the similarities between suret and simulation the concept of suret has an extraordinary correspondance in Orlan’s situation and cannot be replaced by the concept of simulation alone. In spite of the philosophical power of the concept of simulation we need suret to bridge the gulf between West and East in three ways: 1) Suret is a word that in some contexts indicates human face which has obvious implications in relation to Orlan’s art; 2) Sometimes, in its socio-cultural relations in Turkey, the meaning of suret includes references to art, especially painting or photography; and 3) According to Islamic philosophy, suret is the apparent aspect of the divine existence. Therefore suret directs us to a new field of thought which compliments and extends simulation. For an Eastern thinker to properly contemplate and understand Orlan’s Western challenge to the West, and to the East, the concept of suret is invaluable. Suret is an important bridging concept between Eastern and Western art and nowhere moreso than in efforts to understand Orlan’s continuous creation of new faces. A face may exist as a simulation but simulation has not the meaning of face which suret includes.30

VIII. Conclusion

Orlan’s Carnal Art is revolutionary not only because of what she does to her body, but in pointing us to new concepts with which to understand art and our contemporary.31 In this effort, the shadow of Jean Baudrillard cannot be ignored and I hope that further links between Baudrillard’s thought and that of the East may follow. Art never emerges in a transcendental area where it is disconnected from the social, economic, political and environmental problems of the age. Always, beyond a relation of determination, there are interactive dealings between art and multiple other social fields. In analyzing Orlan’s (or any other artist’s work) we should not omit these connections. Art obtains its meaning only in historical, cultural and social contexts – a context which today is transdisciplinary. A sociological approach, for example, is insufficient without contributions from other fields and today, even multiple languages. In sub-fields such as the sociology of arts, working across disciplines and entire cultural systems, we need new notions for new understandings and suret is certainly one of these. Such are the demands of international transdisciplinarity.32 It helps us to point to a consciousness of a time Walter Benjamin never knew, probably would not like, but would certainly recognize. As we continue to try to understand contemporary art, especially that of Orlan, the concept of suret, alongside of Baudrillard’s concepts of seduction and simulation, takes us some distance. If the simultaneous use of concepts from East and West makes the art of Orlan more enigmatic and unintelligible, well, that too is an important task of thought.33 Orland certainly provokes thought – perhaps the best Baudrillardian use of a body of discourse or, in Orlan’s case, a discursive body.

Orlan’s Carnal Art is revolutionary not only because of what she does to her body, but in pointing us to new concepts with which to understand art and our contemporary.31 In this effort, the shadow of Jean Baudrillard cannot be ignored and I hope that further links between Baudrillard’s thought and that of the East may follow. Art never emerges in a transcendental area where it is disconnected from the social, economic, political and environmental problems of the age. Always, beyond a relation of determination, there are interactive dealings between art and multiple other social fields. In analyzing Orlan’s (or any other artist’s work) we should not omit these connections. Art obtains its meaning only in historical, cultural and social contexts – a context which today is transdisciplinary. A sociological approach, for example, is insufficient without contributions from other fields and today, even multiple languages. In sub-fields such as the sociology of arts, working across disciplines and entire cultural systems, we need new notions for new understandings and suret is certainly one of these. Such are the demands of international transdisciplinarity.32 It helps us to point to a consciousness of a time Walter Benjamin never knew, probably would not like, but would certainly recognize. As we continue to try to understand contemporary art, especially that of Orlan, the concept of suret, alongside of Baudrillard’s concepts of seduction and simulation, takes us some distance. If the simultaneous use of concepts from East and West makes the art of Orlan more enigmatic and unintelligible, well, that too is an important task of thought.33 Orland certainly provokes thought – perhaps the best Baudrillardian use of a body of discourse or, in Orlan’s case, a discursive body.

1992

2004

About the Author:

Kubilay Akman is completing his Ph.D. at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Istanbul, Turkey. In the Fall of 2005 he was Visiting Researcher at the Academy of Fine Arts, University of Zagreb, Croatia. He has edited several Turkish art magazines such as Turkiye’de Sanat (Art in Turkey) and Genc Sanat (Young Art). He writes art reviews for rh+ art magazine and Izinsiz Gosteri. IJBS is very grateful to Kubilay for his patient efforts to have this work translated into English.34

Endnotes

1 – The Turkish language version of this paper “Orlan’in Suretleri”, may be found in rh + art, Number 15, 2005. It is also available on the Internet at: http://www.izinsizgosteri.net/asalsayi37/Kubilay.Akman_37.html

2 – I am aware of the difficulties involved in establishing any direct correspondence between Baudrillard’s concepts and Orlan’s art. Indeed, Baudrillard’s thought on plastic surgery and on contemporary art takes his writing in directions directly opposed to Orlan. Both Virilio and Baudrillard could make the case that certain mergers of the body with technology make the body more handicapped. Orlan’s art works in the opposite direction in my view. See also Mike Featherstone. Body Modification. London: SAGE, 2000. I do wish however, despite these difficulties, to point to some important overlaps between Baudrillard’s concepts of seduction and simulation, and the Eastern concept of suret, for those interested in further transcultural readings of Orlan’s work. If this paper presents a challenge to Baudrillard and Virilio, all the better.

3 – Nicholas Zurbrugg. “Marinetti, Chopin, Stelarc and the Auratic Intensities of the Postmodern Techno-Body” In Theory, Culture and Society, Volume 5, Numbers 2-3, August 1999:93-116.

Editor’s note: See also Jane Goodall, “An Order of Pure Decision: Unnatural Selection in the work of Stelarc and Orlan” in Theory, Culture and Society, Volume 5, Numbers 2-3, August, 1999; and in the same issue: Robert Ayers, “Serene Happy and Distant – An Interview With Orlan”; and Julie Clarke, “The Sacrificial Body of Orlan”.

4 – Barbara Rose. “Orlan: Is It Art? Orlan and the Transgressive Act”. Art in America, 81:2, February, 1993.

5 – Ibid.

6 – Kathy Davis. Dubious Equalities and Embodied Differences. New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2003.

7 – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Faust. 1806.

8 – Jean Baudrillard. The Consumer Society. Translated by Chris Turner, London: SAGE, 2003:129.

9 – Ibid.

10 – Ibid.:132.

11 – Ibid.:133.

12 – Jean Baudrillard. Seduction. Translated by Brian Singer, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990:8.

13 – Ibid.:15.

14 – Ibid.:54.

15 – Ibid.:69-70.

16 – Barbara Rose. “Orlan: Is It Art? Orlan and the Transgressive Act”. Art in America, 81:2, February, 1993.

17 – Orlan, Cited in Ibid.

18 – For examples of Witkin’s work see:http://www.zonezero.com/exposiciones/fotografos/witkin2/

19 – See: http://www.chuckpalahniuk.net/

20 – A comparative reading of the works of these three artists side by side might even yield imaginative beginning points to further the critique of modern societies but this is a topic for a separate paper.

21 – See: http://vv.arts.ucla.edu/terminals/flanagan/flanagan.html

22 – See: http://www.yvesklein.org/

23 – See: http://www.crownpoint.com/artists/burden/burden.html (link no longer active 2019)

24 – See: http://www.eyestorm.com/feature/ED2n_article.asp?article_id=38&artist_id=108

25 – A central apsect of traditional North American Aboriginal potlatch involves the host distributing “gifts”.

26 – http://www.dundee.ac.uk/transcript/volume2/issue2_2/orlan/orlan.htm (link no longer active 2019)

27 – http://www.tdk.gov.tr (The Official web-site of the Turkish Language Institute).

28 – Jean Baudrillard. Seduction (c. 1979). Montreal: New World Perspectives Press, 1990:74-5.

29 – Jean Baudrillard, “The Evil Demon of Images and the Precession of Simulacra,” in Thomas Docherty (Ed.), Postmodernism: A Reader. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993:194 ff.

30 – According to some interpretations of suret it means the apparent aspects of the divine existence. And in some Sufi sects the human face has some esoteric meanings as the bases for authentic Hadith of The Prophet Muhammad: “Allah created Adam on his suret (look, form).” There is a profound connection of representation between Allah’s and Adam’s surets in some Sufist interpretations of this Hadith. Human face, its form and unchangable appearance may be accepted as the proof of Allah’s beauty. Hence Orlan’s radical resistance to the beauty concept can also be read as a rebellion against God’s power too. Moreover the relationship between God’s image and creation of the human may be found in Genesis as well.

31 – Editor’s Note: Watching one of Orlan’s performances one if left to wonder if she has taken us a step closer to the artist becoming a machine – Andy Warhol’s dream. Or is it Baudrillard that comes to mind: “Every last glimmer of fate and negativity has to be expunged in favour of something resembling the smile of a corpse in a funeral home…” Jean Baudrillard. The Transparency of Evil. New York: Verso, 1993:45. Perhaps this undecidability about Orlan only increases the enigmatic value of theorizing her art. A rather Baudrillardian place to find ourselves, however ironic it may be in the case of Orlan.

32 – Editor’s Note: Keeping in mind of course Baudrillard’s contention that in the control of concepts (where each discipline keeps them under “house arrest”), “interdisciplinarity merely plays the role of Interpol”. Jean Baudrillard. Cool Memories II (1985-1990). Durham, N.C.:Duke University Press, 1996:19.

33 – See especially Jean Baudrillard. Impossible Exchange. London: Sage, 2001:151. Indeed, Baudrillard may find himself amused to learn that in her performance in an operating room in Japan where she concluded her ten year work in progress called: “The Reincarnation of St. Orlan”, the artist read selections from Baudrillard and Kristeva and others she termed “postmodern” theorists. See: J. Julian Payne. Celebrity Anecdotes: http://www.anecdotage.com/index.php?aid=5503 (link no longer active 2019)

34 -Photographic sources: www.stanford.edu/…/ readings/Orlan/Orlan.html; www.artthrob.co.za/ sept98/listings.htm; http://biografie.leonardo.it/biografia.htm?BioID=537&biografia=Orlan (no longer active 2019); and http://www.izinsizgosteri.net/asalsayi37/Kubilay.Akman_ing.37.html