ISSN: 1705-6411

Volume 9, Number 1 (January 2012)

Author:

I paint people not because of what they are like, not exactly in spite of what they are like, but how they happen to be (Lucian Freud, 2002).

Freud. Francis Bacon (1952)

The aching loss that accompanies the death of an interesting painter is much greater when it marks the ending of a unique point of view. The death of Lucian Freud marks such a passing as did that of his friend Francis Bacon two decades ago. Freud revitalized figurative art by making a unique contribution to it. Throughout a time when humanity became increasingly obsessed with unreal bodies [from wafer thin models to the outcome of muscular self-experiments in supplements and steroids] he remained interested in painting people as they usually happen to be – the imperfect, saggy animals which appear daily in our bathroom mirrors. His portrait of his daughter Bella (1995-96, see image 5), is of an actual young woman far from the ideal represented in magazines yet so beautiful just as she is.

In many of his portraits the flesh protrudes with a astonishing three dimensionality such as his friend Susan Tilley Sleeping by the Lion Carpet (1996). Like so many of his works it is intense yet not unsettling. A protective warmth envelopes Tilley as it does most of Freud’s nudes.

Freud. Sleeping by the Lion Carpet (1996)

Against the strong cultural tendency to censor such images [fat must not be seen] Freud produced images of intense corporality. In 1995 his portrait of Tilley (naked on a sofa) Benefits Survivor Sleeping, caused an enormous stir in England which in the end served to reinvigorate discussions of figurative art. [Benefits Survivor sold for over 17 million pounds to Roman Abramovich at a Christie’s auction in 2008, setting a new record for a living artist]. These are nudes not for art’s sake [he produced a few of those in his younger days too] but paintings about the individual variety of human form and the artist’s ability to represent the unique body before him. For Freud, almost always, the painting was about the individual represented and the challenges that body afforded to the artist. Yet, in the end, when we line up many of Freud’s nudes we find a remarkable similarity in his subjects which has to do, I think, with the melancholy nature of any human individual. Freud chose to paint from his intimate world and I think the care he shows for his intimates is part of the warmth that envelopes informs them: “I work from the people that interest me and that I care about, in rooms that I live in and know” (Lucian Freud, 2002).

Freud. David and Eli (2004)

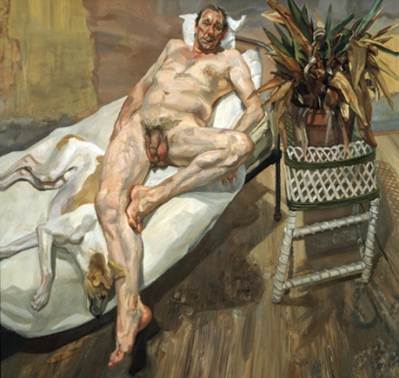

Remarkable in Freud’s oeuvre are the male nudes. Again, working against the grain that has long suppressed the nude adult male form in realist painting, Freud rendered a number of strikingly direct and candid images. Freddie Standing (2001) is an image of pathos and most of his male nudes are paintings of men shown as vulnerable subjects – the way women have been shown in painting for hundreds of years. These included several nude images of himself my favourite of which is the ironically titled Painter and Model (1987).

Freud. Painter and Model (1987)

Nude self portraits seem an essential aspect of Freud’s work which became a highly self conscious practice. We do not find many props or idealized subjects in costume in his works [for which realism has shown an immense historical fondness]. What we find in the main are portraits in which the studio is also represented. Each of these says to us ‘This is a portrait, made by me, of this person, as I saw them, naked and vulnerable, in my studio’. David Dawson’s photograph of Freud painting his daughter Bella captures both the intensity and slowness of the artist’s process.

David Dawson. Lucian Freud in his Studio [painting his daughter, Bella] (1995)

However, Freud did not always do as well with portraits of people he did not know well. While he does capture the detached coldness of the Queen his portrait of her is little more than a sketch when compared with the more affectionate images of his intimates. His painting of Kate Moss is another example of the difficulty he faced in painting people from outside of his immediate circle as was his effort to render the critic John Richardson. The problem with painting people he did not often see is no doubt linked to the fact that he liked to work very slowly in prolonged multiple sittings. His portrait of the Queen, Richardson, and Moss did not afford him this luxury. Moss is one of several pregnant women he painted.

Freud. Kate Moss (2002)

Lucian Freud worked against the grain in his deep and concentrated relation to the history of painting and in so doing became the most remarkable painter of human flesh since Rembrandt. He also worked against the grain of a culture of idealized bodies where images of fat or pregnant women are considered publishable only by sub genres of the pornography industry. And while doing so he painted exquisite vulnerable male nudes.

Perhaps his greatest contribution, as a self acknowledged realist, was his betrayal of much of the mythology of “realism”. For Freud the human mask extended beyond the face [where he usually began his portraits] and extended to the entire length of the body – even naked we remain largely unknowable to the other. In pushing the nude to its extremes – to the point of catastrophe – Freud calls upon the strong sense of humanity within each of us – not far from pity – while forcing us to want to look at these less than ideal representations for the sumptuous expressions of paint which each of them is. His work calls upon us to appreciate the melancholy creature we are as much as it calls on us to admire the technical skill of the painter.

Freud. (Self Portrait) Reflection with Two Children (1965)

With the passing of Lucian Freud we lose a very important image maker – one who was deeply concerned with art’s most adventurous soul. He gave us a new understanding of the portrait and what it might yet achieve for the painter, the sitter, and for art. It is not an overstatement to call Lucian Freud the Rembrandt of our age.

Lucian Michael Freud (December 8, 1922 – July 20, 2011)