ISSN: 1705-6411

Volume 3, Number 1 (January 2006)

Author: Dr. Mike Grimshaw

… a roaring motorcar, which runs like a machine gun, is more beautiful than the Winged Victory of Samothrace. …We will glorify war – the only true hygiene of the world – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchist, the beautiful ideas which kill… We will destroy museums, libraries, and fight against …feminism, and all utilitarian cowardice. The oldest among us are thirty; we have thus ten years in which to accomplish out task. When we are forty, let others, younger and more daring men – throw us into the wastepaper basket like useless manuscripts.1

The architecture of… Adolf Loos epitomised the new spirit which rejected decorative excess. The functionalism and simplicity of the buildings contrasted strikingly with the highly ornamented façades of nineteenth century Vienna. Loos’s Michaelerplatz Haus was erected opposite Emperor Franz Josef’s ornate residence. So unimpressed was the Emperor by the stark rigour of Loos’s shop building, that he is said to have closed the curtains in the Hofburg to keep it out of sight.2

The assassins of September 11th made no demands. Fundamentalism is a symptomatic form of rejection, refusal; its adherents didn’t want to accomplish anything concrete, they simply rise up wildly against that which they perceive as a threat to their own identity.3

What is to be done, at present? The question is on everybody’s lips and, in a certain way, it is the question people today always have lying in wait for any passing philosopher. Not: What is to be thought? But indeed: What is to be done?4

I. Introduction

Three moments in twentieth century thought which help us to rethink the relationship between religion and terror are Adolf Loos’ proclamation that to be modern is to be unornamented; Filippo Marinetti’s call for the purity and modernity of speed, and Jean Baudrillard’s understanding that the “uncertainty principle does not belong to physics alone; it is at the heart of all our actions, at the heart of ‘reality’”.5 All three came together as the expression of a religare (a binding together) with the attack of September 11, 2001 when postmodernity ended with an act aiming for the return of an alternative modernity, obsessed with purity and the speed of destruction, and signaled by the symbolic destruction of the twin towers.

Adolf Loos. Michaelerplatz Haus.

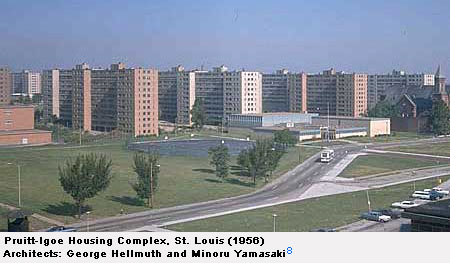

Terrorism is a self-expression of modernity and the rejection of that which is unnecessarily ornamented. The modernity of terrorism is expressed in its obsession with purity, destruction and speed, and involves the symbolic destruction of that, which it believes, is threatening. Terrorism is the articulation of alternative “modernities” – not, as is often mistakenly believed, that “so many radical Muslims [want] to fight to return to the seventh century”.6 These acts of destruction are similar to that which demolished the Pruitt-Igoe housing schemes – an attack from within that which has created modernity so as to clear the space to create an alternative.7

Pruitt Igoe. Housing Complex. St Louis, 1956 7.5

Demolition of Pruitt Igoe 1972

The central problem facing any response is therefore to acknowledge that terrorism is itself a symptom of modernity and in fact is more likely to be carried out by those who have been “modernized” and “westernized” – and who often reject Western modernity in favour of an alternative one. To eradicate terror would entail the eradication of modernity itself. Indeed, as Baudrillard points out, the attackers of September 11, 2001 were masters of modern systems and technology:

…a new terrorism has come into being, a new form of action which plays the game, and lays hold of the rules of the game, solely with the aim of disrupting it. … they have taken over all the weapons of the dominant power. Money and stock-market speculation, computer technology and aeronautics, spectacle and the media networks – they have assimilated everything of modernity and globalism, without changing their goal, which is to destroy that power. …Suicidal terrorism was a terrorism of the poor. This is a terrorism of the rich. This is what particularly frightens us: the fact that they have become rich (they have all the necessary resources) without ceasing to wish to destroy us.8

What should also be remembered is that the fact of this paper (and of so many others), all the media discussion, books, articles and debate, are but a confirmation of the success of terrorism. This is because we have actually redirected our energies, interests and resources to inversely “legitimate” and “authenticate” what has occurred – and that we live in “terror” of what may eventuate.

In order to expand the dialogue on terrorism we can look to the theories of Loos and Marinetti and the ways in which they may have – perhaps unwittingly – driven the link between religion and terror. As part of this discussion these theories must also engage the radically different approach to terrorism by Jean Baudrillard and those, like Georges Bataille, who have influenced his work. It is out of this confluence of theory that we may perhaps begin to rethink religion and terror. This will lead us to ask if it is still possible to articulate responses in secular western democracies such as New Zealand, or can the West now respond only by “terrorizing itself”.9 Baudrillard problematized the very possibility of this choice some time before the events of September 11, 2001:

Islamic fundamentalism – a providential target for a system which no longer knows what values to subscribe to – has a pendant in Western integrism, the integrism of the universal and of forced democracy, which is equally intolerant, since it, too, doesn’t grant the other the moral and political right to exist. This is free-market fanaticism, the fanaticism of indifference to its own values and, for that very reason, total intolerance towards those who differ by any passion whatsoever. The New World Order implies the extermination of everything different to integrate it into an indifferent world order. Is there still room between these two fanaticisms for a non-believer to exercise his liberty?10

This paper argues that terrorism is a form of religare (a binding together) occasioned and encouraged by modernity. Terror is in fact a form of religious impulse and belief that arises out of the Purist and Futurist roots of modernity. I begin with a discussion of the Purist and Futurist debates and the associated work of Adolf Loos in order to highlight the fundamentalism [the literal reading and assertion of “the fundamentals”] that informed modernism from the beginning. I then assess religion in modernity and modern religious fundamentalism’s attack on secular modernity. This is followed by a discussion of terror, religion and modernity wherein terror is itself understood as a form of modern religare, involving symbolic acts to which our response validates. Terrorism is understood here as the embodiment of a modern religion of fear. This leads us to understand terrorism as the response within modernity to competing claims of the real; which raises the question of the possibility of disenchanting symbolic action. Such would seem to be a necessary path for a country like New Zealand. But as Baudrillard points out: “The revolution of our time is the uncertainty revolution”11 and this makes the outcome a very undecided one for the West.

II. “Ornament and Crime” and Religion

In 1908 the Austrian Architect and thinker Adolf Loos delivered an influential paper laying out the principles for what became the modernist ethic.12 Who, asked Loos, in this day and age wilfully decorates themselves and their environments with unnecessary decoration and ornamentation in the manner of the undeveloped child or the uncivilized Papuan? Only two groups: those with criminal tendencies and the degenerate aristocrat. To be modern, to be progressive, to be cultured, to be civilized was and is to live your life with control, order and discipline. It is to live your life without the support and excess and distraction of unnecessary ornamentation; and that ornamentation, post-Nietzsche, included God. Loos’ claim was that unnecessary ornamentation was a sign of arrested cultural development, the expression of a primitive outlook, the signal of a criminal tendency or the mark of a degenerate aristocrat. This resulted in unnecessary ornamentation being labelled a sign of deviancy. For Loos, the child or “the Papuan” may be free to scrawl and decorate because they had not yet “come of age” in either a physical or cultural sense. Those who lived in a mature, civilized culture having achieved adulthood (culturally and developmentally) would only unnecessarily disorder their world through deviance.13 While Nietzsche had proclaimed the death of God some twenty years earlier and Marx had made him an opiate, Loos now made him an unnecessary ornament. God was no longer the great architect, the one who ordered the world. Rather, in an act of Gnostic reversal, God was seen at that who disordered humanity. What Loosian modernism does is introduce the possibility of a modernist secular fundamentalism that reads “the world” as it “literally is”.

Modernism is an act of utopian “progressive” secularism, an attempt to order that which God was seen to disorder: an act of humanism over and against religion. It is the secular apocalypse, the attempt of living in an immanent kingdom of the absent God – as Thomas Altizer, prominent 1960s proponent of the death of God would claim:

If there is one clear portal to the twentieth century, it is a passage through the death of God, the collapse of any meaning or reality lying beyond the newly discovered radical immanence of modern man, an immanence dissolving even the memory of the shadow of transcendence.14

Altizer states that out of this has “come a new chaos” of Nietzschean-forecast nihilism.

Loos’ title was wilfully mistranslated by those of Purist sympathy in the France of Le E’spirt Nouveau as “Ornament is Crime”.15 This act changed the nature of modernism as those who followed the Purist manifesto came to assert a form of sub-Nietzschean nihilism. If the Loosian aesthetic is one of less, the Purist aesthetic is one of imposed loss. Loos looked to banish what was perceived as the unnecessary; his is a reduction in the name of culture and civilization, an assertion of a humanist, modern, progressive ethic. The Purist, in contrast, came to reduce for reduction’s sake; theirs is a machine aesthetic in that technology is the raison d’etre. While the Purist ethos is that of white purity (and control), the Loosian desire to control is not far removed from that of Marinetti and the Furturists who worship at the altar of secular modernism.

III. The Challenge of Futurism

The banishing of ornament, the signal of God as deviance, the flat roof of an immanent transcendence, the Purist white wall, each sought not only to banish the chaos of fin de siecle ostentation and the horrors of World War One, but were also an attempt to embrace the new hope of technology and a Futurist inspired machine age. In Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto: “The New Religion – Morality of Speed”, speed is the new location and expression of divinity. Marinetti, viewing the Great War as “liberating”, expresses a Futurist morality that: “…will defend man from the decay caused by slowness, by memory, by analysis, by repose and habit. Human energy centupled by speed will master time and space”.16 This creates a new secular religious response: “If prayer means communication with the divinity, running at high speed is a prayer. Holiness of wheels and rails. One must kneel on the tracks to pray to the divine velocity”.17 This also means that “one must persecute, lash, torture all those who sin against speed”.18 Futurism deepens and extends Loosian modernist fundamentalism raising it to a kind of secular religion. Out of this Marinetti expresses a new Futurist-Purist doctrine of modernity:

Speed, having as its essence the intuitive synthesis of every force in movement, is naturally pure. Slowness, having, having as its essence the rational analysis of every exhaustion in repose, is naturally unclean. After the destruction of the antique good and the antique evil, we create a new good, speed, and a new evil, slowness. Speed = synthesis of every courage in action. Aggression and warlike. Slowness = analysis of every stagnant prudence. Passive and pacifistic. Speed = scorn of obstacles, desire for the new and unexplored. Modernity and hygiene. Slowness = arrest, ecstasy, immobile adoration of obstacles, nostalgia for the already seen, idealization of exhaustion and rest, pessimism about the unexplored. Rancid romanticism of the world, wandering poet and long-haired, bespectacled dirty philosopher.19

Marinetti’s linking of speed, destruction, modernity and war as the hygiene against the unclean slowness of that seen to be in decay sits at the heart of religious terror. This is an interesting overlap between the secular modernist fundamentalist of a century ago and the modern religious terrorist. Baudrillard, comments on this in way that makes the link explicit noting:

…that generation you see everywhere, in all latitudes, running, jogging or walking, and high on phobic concern for their bodies. This is the New International Hygienic Order…This is the hygiene of the Assassins.20

(The self-terrorism of the West is therefore just another version of the terror that seeks to eliminate the West in the name of a religious hygiene).

Marinetti’s Futurism can be read in tandem with Loos prophetical statement: “I have discovered the following truth and present it here to the world: cultural evolution is equivalent to the removal of ornament from articles in daily use”.21 This Loosian truth signals the modernist desire to control and order all that is disordered: religion, sex and ornament. All are to be removed from daily use – all (as ornament) are no longer “organically linked” nor “an expression” of our (modern) culture.22 Loos links the absence of ornament to a religious view by articulating what is clearly the salvific status of non-ornamentation. The absence of ornament is that which will enable humanity to create the city of fulfilment where, having won through to lack of ornament: “…the streets of the town will glisten like white walls. Like Zion, the holy city, the metropolis of heaven. Then we shall have fulfilment”.23 As Baudrillard notes of the “immanence” of modernity:

The whole movement of modernity, its negative destiny, lies in the fact of transcribing all that was of the order of the imaginary, the dream, the ideal and utopia into technical and operational reality.24

Renato Bertelli Futurist Bust of Mussolini

Those who live in this new Zion of secular modernity are aristocrats – not the ornamented degenerate aristocrats Loos is opposed to, but a form of Gnostic-elite; aristocrats who are evolved beyond those who have need for ornamentation. Loos tellingly uses the example of an old woman with a roadside shrine. He claims that the revolutionary confronted with this would challenge her with the words “there is no God”; but the Loosian atheist aristocrat “raises his hat on passing a church”.25 This means religion is seen as a form of cultural evolution – in a sense it is “the opiate of the masses”. Not being a revolutionary, the Loosian aristocratic modern has no desire to tear down the ornament and attempt to make “aristocrats” of those who are as yet unable and unprepared to adopt such a position. Those who have moved on from the peasant world – that is, those who have left the village mentality and existence behind and become urban (the Loosian location of modernity) – will only wilfully turn to unnecessary ornamentation if they are degenerate aristocrats or have criminal tendencies. The church deserves true aristocratic modern respect and good manners for what it symbolizes – but the true aristocratic modern is beyond needing it. For only the revolutionary will wish to erase the past, the aristocrat is aware that it can be and always is being supplanted.

IV. Toward a Loosian Theory of Religion in Modernity

If we look back over the century of modernity, we can re-read it as a Loosian battle where religion comes to be viewed as a form of ornament. Contemporary religious fundamentalism is another form of Loosian-like move against ornament, but it is an inverted move, whereby the modern unornamented world is seen as a form of unnecessary ornamentation. In response, modern religious fundamentalism often retreats to what Loos or a secular modern would see as a world of ornamentation, a costume of literalism which draws on pre-modern belief – but for very modern purposes:

O ye who believe! When ye meet a force, be firm, and call Allah in remembrance much (and often); That ye may prosper. God, who sent the book unto the prophet, who drives the clouds, and who defeated the enemy parties, defeat them and make us victorious over them. Our Lord! Give us good in this world and good in the Hereafter and save us from the torment of the Fire! [Koranic verse]. May God’s peace and blessings be upon Prophet Muhammad and his household.26

The New Age, seen from a secular modern Loosian viewpoint, can be understood as the return of unnecessary ornamentation. In a physical manner, buildings, lives and bodies became newly unnecessarily ornamented – all are costumed, tattooed, decorated. In a manner similar to modern religious fundamentalism, the interior Raumplan of spirituality became inverted over and against the white walls of modernity. Religion and secularity are now both seen as forms that the necessary ornamentation of postmodern spirituality and the New Age reacted against. Conversely, the return of conservative religious movements signals a reaction against such decoration. Viewing both the inverted interior spirituality of the New Age and the lingering late modern secularity as forms of unnecessary ornamentation, modern (and postmodern) religious conservatism attempts to both banish what is seen as unnecessary and, paradoxically, enforce a modernist-derived order of necessary ornamentation. This “soft modernism”27 can hold together both Peter Berger’s desecularization and Steve Bruce’s continued secularization theses. Both can view the other as forms of costume that limit the Loosian pursuit of the expression of “our time” – they are types of “bad form”. Therefore, what sits at the heart of the modern condition (whether modern, postmodern, anti-modern or soft modern) is the question of the necessity or otherwise of ornament; and the continuing, debatable, contestable question of what exactly constitutes ornament when, as Loos demanded, we “think and feel in the spirit of our time”.

V. Rethinking Terror, Religion and Modernity

To respond to the religare of terror in modernity, we could turn to the Loosian response to the roadside shrine: the confrontation with that which posits an alternative to secular modernity. Unfortunately, we tend to respond like the revolutionary and see it (the religare of terror) as an affront. Rather, we could view it for what is actually is, the survival of religion as a provocation to the modern world, seeking affirmation in and from the attempt to destroy it. An alternative for secular modernism is to remember what Nietzsche claimed caused the death of God: not the frontal attacks and dismissals, but rather, in the end, the turn of indifference. Thus, instead of the current ongoing exchange of affirmation in which both the fundamentalist terrorist and those who respond symbolically affirm each other, we could seek to adopt a position of indifference. This of course does not mean fundamentalist terror will fade away completely, but it could lead to its marginalization from the everyday, whereby terror is located as sectarian. Every response to terror actually affirms the destruction that takes place as being necessary for it and its claimants to be noticed.

Here we can look to what Brian Tamaki has done with a small (7000 strong) sectarian religious movement, Destiny Church, in New Zealand. Understanding the importance of the mass media to articulate (a media-derived) legitimacy – to be seen is to exist – he moved into the public media, creating a deliberately provocative presence on both television and the internet28 , by opposing the proposed extension of civil unions to homosexuals and the reform of prostitution laws. His central message decries moral and spiritual decay, calling the nation back to a proposed theocracy of the kingdom, allied with a strongly protestant gospel of prosperity. What makes Tamaki important is his recognition that public appearance is, in a postmodern-inflected world of image and spectacle, itself an act of self-legitimacy. To appear on television, in a localized version of American televangelism, even if within the early-morning dead-zone of church-funded “infomercial” preaching, is to recognize that it is the appearance on television that creates the real for those uninitiated in post-structuralist semiotics. For those able to decode such action, his infomercial televangelism is a simulacra; but for those who do not decode, this becomes a form of “real presence”. He “made real” his presence, in what was a carefully stage-managed “return to the real” – but as simulacra that was based – albeit vigorously denied – in good modernist, futurist fashion, on the hyper-real mythic history of Mussolini’s act of legitimacy: his fascist march on Rome of 28 October 1922.

Tamaki’s simulacrum of this occurred on 23 August 2004 with a rally of his Destiny Church followers down the main street of the capital, Wellington, culminating in a march on Parliament, accompanied by body-guards and lead by a crowd of predominantly Maori and Pacific-island men, in black t-shirts, waving their fists and chanting “enough is enough”. This courting of public notice by partaking in what was a pseudo-event, a spectacle, was an act of public terror with its fascistic overtone and black-shirted associations of masculinity, power and the war-dance confrontation of a mass haka.29 It worked – the indifference of the general public and the media to Brian Tamaki lasted only as long as he and his cult were not a pseudo-event, were not a public spectacle, as long as they did not evoke a response of fear that was out of all proportion to the size of his organization.

In the months since his pseudo-spectacle he has become a form of alternative legitimate voice of religion in New Zealand – the one that the media turn to because of the “terror” of his provocative stance. To counter the hyper-real terror of Bin-laden or Tamaki is actually to seek to control the reproduction of the hyper-real – the circulation and mass-media production of the image. Mass-media provides a hyper-real “religare” – a binding together, a communal presentation and affirmation as to the efficacy and indeed legitimacy not only of the circulation and presentation of the event, but of the event itself. Yet conversely, to seek to limit the spectacle is to enforce the control of image and truth that is sought by the terrorist.

In effect, terrorism occurs and is “justified” when the spectacle is reported and repeated. This is because it is in the religare of the mass media that terrorism really occurs. It frees the act of terror and intimidation from its physical location in the event and makes it national – and increasingly transnational. This means we now “believe” in terror because we respond to its representation: that is, to its image. It has actually become a form of religare that binds us all together – “we believe in terror” – and in our belief we give it a form of efficacy and legitimacy. Yet is important that we remember that a religare binds different groups together in different ways. Therefore, if religion arises in a multiplicity of ways from religare (that which binds us together) then terrorism itself has become a cause of – and expression of – a new global religion that is basing itself on a theory of exchange and sacrifice to institute an alternative modernity. Or rather, to institute alternative forms of modernity that challenge what is seen as the chaos occasioned not only by secular modernity but also the conversant multiplicity of chaos that arose out of postmodernism and its turn to the multiplicities of others and the pluralism of truth and identity. Terrorism is a hyper-real apocalyptic event that provides an alternative teleology. In fact, after the event we now live in terror of the “pseudo-event”: not that which has occurred, but rather something that we believe may or will “occur”. In many ways we are living in our own version of millennial apocalyptic cults, seeking an eschaton that will affirm that our hopes and fears are correct.

VI. The Symbolic Nature of Terror

Baudrillard, writing in The Spirit of Terrorism, mentions the importance of not so much providing explanations but rather the importance of “an analysis which might possibly be as unacceptable as the event, but strikes the …let us say, symbolic imagination in more or less the same way”.30 What Baudrillard wants to emphasize is the symbolic nature of acts of terror – and the importance of what is destroyed or attacked. In discussing the attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon, he stresses that we should not forget that the focus was actually the symbolic object, rather than the architectural object.31 This leads him note that “most things are not even worth destroying or sacrificing. Only works of prestige deserve that fate, for it is an honour”.32

While we must discuss the central issue of the sacrificial act, I also think that this insight is an important element for considering actions undertaken by Maori activists in New Zealand over the past decade. In every case – the theft and threatened destruction of the painter Colin McCahon’s iconic Urewera mural in 1997, the chainsaw attacks on the iconic tree on One Tree Hill in Auckland in 1994 and 1997, the decapitation of the statue of the colonial Premier John Ballance during the 1995 Moutoa gardens protest, the attack on the America’s Cup in 1997 and the activist Tama Iti’s shot-gunning of the New Zealand flag, in front of a governmental delegation and captured on television news in January 2005 – all point to the possibilities of acts of symbolic terror associated with Maori radical movements. Each was a symbolic attack upon something representing prestige – but a prestige that is perceived as an affront.33

As Baudrillard notes: “Terrorism invents nothing, inaugurates nothing. It simply carries things to the extreme, to the point of paroxysm. It exacerbates a certain state of things, a certain logic of violence and uncertainty”.34 That is, the effect of terrorism is in its effect – in other words, it is our response that makes what is terror “terror”. We “believe” in its stated aims by responding as if it is terror – in effect legitimizing it by making it an authentic act of symbolic affront and a sacrifice. To accept the offer of the gift of terror and death, to accept the gift of symbolic affront is to participate in the logic of exchange which affirms the action of the terrorist as both legitimate and of worth. This results in a situation whereby both “terrorism” and “the war on terror” actually affirm and legitimize each other because global disorder is both believed in and perceived as “the norm”. It is also a situation whereby both sides – “terror” and “war on terror” – are each seeking to impose alternative forms of “order” which are viewed as the solution to the disorder which is perceived as forcing the act of terror in the first place. In other words, attempts to impose “order” merely serve to perpetuate the disorder that each form of order seeks to overcome. We end up with a terrorist war on terror, all the more terrorist for the fact that it now seems endless. To impose a Hegelian-derived dialectic, where “terror” is the thesis and “war on terror” is the antithesis, the synthesis is this hyper-real “terrorist war” – a synthetic event that is increasingly taken as an end-state.

For Nietzsche the “death of God” was caused by human indifference – and indifference to religion (specifically Christianity) as the expression of that God. Today in a world where we seem to believe in the religare of terrorism, that “terror” has become the new global god we seek to oppose or affirm. In a sense terror is actually the religion of globalization. That is, terrorism occurs and exists as the religare of globalization, that which occurs out of it and authenticates it, that which provides an ontology of violence and uncertainty, that which justifies the expansion of globalization by its occurrence. As Baudrillard notes: “And it is the real victory of terrorism that it has plunged the whole of the West into an obsession with security – that is to say, into a veiled form of perpetual terror …The spectre of terrorism is forcing the west to terrorize itself”.35 This religare of fear, this self-affirmation by terror is actually a response that arises out of the meaninglessness of modernity – and the rejection of the cosmopolitan pluralities offered by postmodernism. In effect the recourse to terror is the rejection of both the plurality of contemporary society and the challenge of “the other” that pluralism offers. It is the return to the central question presented by modernity: that of meaning in the face of indifference. As G. Clarke Chapman put it, the issue with the rise of terrorism – and its response – is that of what to do “that enables us to cope with the acute sense of vulnerability imposed by engulfing modernity”?36

In response to this question, I believe we need to note that the erosion of old norms and stabilities, the rejection of the cosmopolitan uncertainties and provisionality of postmodernism, allied with the “indifference” that leads to the death of God, have all resulted in a sense of communal identity and meaning being provided by the new religion of fear. Over the past fifteen years since the decline of the threat of the cold war, there has been the media-driven explosion of a succession of new eschatological fears, of disease, pandemics, global warming or cooling, biogenetics, Y2K, immigration etc, which are but forms of global terror which seek to overcome the indifference of the western world.

Terrorism is the embodiment, the clarification, of this indifferent religion of fear, this religare of terror. In other worlds, fundamentalist terror is manufactured, presented and believed in as the religion of the modern indifferent world. Its worship of both the speed of destruction and of the speed of spreading its event-message using global media, allied with its focus on a destructive purity, make it the latest embodiment of Futurism.

VIII. Religion, Terror and Sacrifice

To disenchant terrorist discourse also means, in a multi-religious and multicultural society, the necessity of disenchanting the state and public rhetoric. The turn to talk of religion and spirituality, that talk of re-enchantment and desecularization, not only serves to act as public space for religious diversity to state their claims of communal legitimacy, it also provides a public space for the religion of terror and terror discourse. To disenchant is not to dismiss the various religious claims or affiliations, but to effectively seek to secularize them into the realm of privatism. Yet in order to do this we need to be also aware of the claims of the sacred, especially in claims of sacrifice and transgression that exist still within our society – and which are repositioned into the public sphere by acts of terror.

Georges Bataille offers a provocative take on the challenges of sacrifice and transgression, in which the sacred unleashes itself in acts of passion which are contrary to reason. He notes the links of horror, terror and the sacred and how, in the contemporary world, with the reduction to symbolic passion in our religion we have attempted to domesticate our fascination with death and destruction that sits at the heart of religion. This is the basis of the religare of terror – our fascination with death as sign and symbol of the sacred. Therefore the challenge of terror is the return of the sacred as transgressive in a world seeking to limit and contain it, to reduce it. The problem is that we fail to see acts of terror as acts of exaltation and intoxication in the sacred, failing to acknowledge Bataille’s claim for the transgressive eroticism of terror:

The inner experience of eroticism demands from the subject a sensitiveness to the anguish at the heart of the taboos no less great than the desire which leads him to infringe it. This is religious sensibility, and it always links desire closely with terror, intense pleasure and anguish.37

This is why terror has become the new global religion. It reflects and provides the religious sensibility in the contemporary world – it transgresses the space given to religion in the postmodern turn and rejects both the restraints of controlled plurality and the turn away from plurality in the turn back to a new modernity. Today, terror is a religion that acts as transgression and taboo to both modernity and postmodernity. In a sense, following the Nietzschean nihilism of Beyond Good and Evil we now exist in a world of taboo and transgression, a world of sacred violence. As Bataille notes: “the transgression does not deny the taboo but transcends and completes it”.38 In this we need to now view the transgression of terror as that which transcends and completes both taboos – those of death and of religion/sacred in public space – in the modern world. As “the taboo is there to be violated” and is “at the very least …the threshold beyond which murder is possible”,39 our taboos on public death and public religion are in fact those which paradoxically issue a form of demand for the transgression of terror – and the terror of transgression. In effect, notes Bataille, for our profane world to exist we require the complementary acts of transgression that exceed its limits but do not destroy it: “the profane world is the world of taboos. The sacred world depends on limited acts of transgression”.40

This means that acts of terror are acts of transgression for the expression of the reality of the sacred world. In other worlds, acts of terror are a form of sacrifice. What the act of sacrifice does is not a killing but rather a relinquishing and a giving. What is sacrificed is what is useful – it “restores a lost value by relinquishment of that value”.41 As bin Laden would have it:

When you talk about the invasion of New York and Washington, you talk about the men who changed the face of history and went against the traitors. …These great men have consolidated faith in the hearts of believers and undermined the plans of the crusaders and their agents in the region. Terrorism against America deserves to be praised because it was a response to injustice, aimed at forcing America to stop its support for Israel, which kills our people.42

The acts of terror are, from a religious viewpoint, acts of sacrifice: they give up what is useful – the life of the terrorist, the life of the believer, the sacrifice of people in the profane world – in a manner of transgressive action that seeks to transcend the taboo on violence, death and the sacred. As Bataille notes: “The sacrificer declares …I call you back to the intimacy of the divine world, of the profound immanence of all that is…”.43

The spectacle of terror is therefore on one level the intimacy of sacrifice in the intimacy of our daily lives, in the intimacy of our living rooms, in the intimacy of our public and private spaces. It is on one level, as Bataille states of sacrifice, “the communication of anguish”.44 So what is this anguish? Perhaps it is as Slavoj Zizek notes, the cry of anguish of sacrifice, of terror, of violence. Furthermore, that our transgressive avidity for these is our passion for the “Real” – that which he notes Alain Badiou as claiming is “the key feature of the twentieth century”.45 This passion for the Real is what sits at the heart of Loos’ call for the overthrow of unnecessary ornamentation; this passion for the Real sits at the heart of the Futurist worship of the cleansing effect of technology, war and death; this passion for the Real is what lies in modernity’s rejection of transcendence – and in Postmodernity’s rejection of modernity’s secularity. In effect, the dualistic battle in modernity between what is seen as order and what is seen as chaotic is this battle over what is Real and where the Real is located. Violence, taboo, transgression and sacrifice are those acts that serve as both statements of the Real – and the rejection of what is perceived to be non-Real. Acts of terror, made possible by the space given in postmodernity for the articulation of varieties of transcendent “Real”, are an act of the rejection of these possibilities in a challenge of what is seen as the Real. Yet in their symbolic intention, they participate in the postmodern spectacle as an attempt to evangelize by effect. The passion for the Real and the attempt to represent it are actually transgressive to modern world where we attempt to keep the Real controllable by not confronting it. The response to the rise of transcendence as the location of the Real was not to confront it but rather to seek to splinter it by postmodern tolerance. Yet all this did was to give consent to those who sought to destroy even the possibilities of competing Reals.

In effect, contemporary terrorism is the Real of modernity (a battle beyond good and evil, of order and chaos) confronting itself with the non-reality of terror and spectacle that act as transgressive to that which we seek to hold as Real. The effect is not concerned with the reality of the chaotic act, but rather with the chaos that is the response to the reality of the act. In effect we say “we cannot believe this act has occurred” and this stating of our inability to believe in the Real is the chaos that the act of terror seeks. We then search to ascribe a meaning to the event that may mean we claim to see the reason behind the act, the “cry of anguish” that caused this act. To ascribe meaning to the act is to order it, in effect to attempt to “make it real” – and in making it Real paradoxically giving a form of inverted value and meaning to the actions and beliefs of those who undertook it. Yet often what happens in response is the turn away from the liberal tolerance of dissenting beliefs that (perhaps) marks off a Western sense of the Real: a form of order that exists by ordering chaotic elements within pluralism. Yet the act of terror is a rejection of Western liberal pluralism, a rejection of the type of Western order that secularizes its taboos and transgressions.

IX. The Response to Terror.

The type of modernity in which we currently find ourselves is, in a Zizekian sense, one where we have a series of competing claims as to both the validity and location of the Real – and a series of competing claims as to what are acceptable actions to institute its recognition by the wider population. Fundamentalist terror sees what it seeks to destroy as chaotic, as unnecessary, as an affront to what is Real, what is ordered, what is necessary. Fundamentalist terror is the violence of the Real in the service of what is seen as the necessary alternative. The type of symbolic violence undertaken is a reflection of the type of claims of reality being made. Symbolic action as has been undertaken so far in New Zealand reflects a society that is secular by inclination. The Real is contained in symbolic action that can be reported and represented as secular in effect and motivation. Other acts of symbolic action in New Zealand such as desecration of Jewish graves, and graffiti attacks and vandalism of mosques and synagogues can, in a secular society, be contained as criminal acts of a non-legitimate extreme minority. The challenge presented by Destiny Church is not its symbolic nature, but rather the media response that gives credibility to religiously motivated symbolic events as being effective – and as being a means of effecting a form of legitimacy. Yet paradoxically, what will keep Destiny under control is its obsession with a gospel of prosperity – they will not seek to destroy the type of society that they believe will reward them. The danger to a country like New Zealand is the recourse to symbolic violence by those marginalized by both belief and culture – and yet given postmodern tolerance for their intolerant beliefs. The Real of the modern secular pluralist state is ever open to the challenge of the competing modernity of the religious Real that understands the nature and efficacy of symbolic violence. As Paul Piccone and Gary Ulmen noted in response to September 11:

The first thing that will have to go is the criticism of the concept of tolerance for the intolerant – and therefore of its pseudo-universalism. Tolerance is a particular western value, which applies only to those who practice it. It excludes not only those who reject it, but also those who tolerate its rejection.46

The religion of terror is linked to the religion of modernity, the belief in the pluralist secular nation state, the belief in a future that unfolds through rationality and progress – and in particular to a distinct form of western modernity. The failure of the postmodern can now be seen as the failure of the extension of tolerance to the intolerant, to those who seek to reject that which enables them to dissent. The recourse to symbolic violence is the challenge of the transgression of the taboo of intolerance; that which seeks a response that will assert the validity of the claims of the Real being made by the terrorist. As Baudrillard notes: “The tactic of the terrorist model is to provoke a surplus of reality and to make the whole system collapse under it”.47

To oppose the surplus of the reality of taboo and transgression that is to be found in the act of terror, the system under attack needs an alternative Real that can neutralise any attempts to impose any religious Real upon the general public and the nation. This occurs either by the symbolic actions that terrorise the liberal State’s fear of being viewed as intolerant, or in specific actions that by act of violence seek to spread the terror of the Real through the religare of the mass media and so constitute the grounds for a new religare of terror. The challenge is that it is the freedom of the mass media that allows the circulation of the spectacle of terror – yet to limit the spectacle is to enforce the control of image and truth of the kind sought by the fundamentalist terrorist.

Contemporary terrorism is not a challenge against modernity, but rather a challenge that rejects the offer of postmodernity, an offer made by the post-Christian West and yet rejected by those who that West sought to include. What is offered in the act of fundamentalist terror is the challenge of an alternative modernity, an alternative way of ordering the chaos of life, an alternative belief system that uses the synthesis of mass media and terror to provide a new religare of terror that, in our response, serves to validate, from the point of view of the terrorist, the sacred necessity and justification for the act of terror: “We realized from our defence and fighting against the American enemy that, in combat, they mainly depend on psychological warfare. This is in light of the huge media machine they have”.48

To oppose the religare of terror the state may opt to secularize symbolic recourse as criminal behaviour, as has been the case in New Zealand, in effect trying to neutralize terrorism claims to efficacy as religious act and as religare, through a response of indifference. Secondly, it may be recognized that the privatization of belief and culture that occurs in modernity can also serve to allow the legitimization of intolerance within those groups. A cosmopolitan society is therefore confronted with the reality that calls for religious and cultural difference which can locate and express themselves in statements and actions of intolerance. Thirdly, this means that the secular religare of a cosmopolitan society will result in symbolic acts by those who seek to reject it. With the increasing recourse to religion as a form of identity politics (beliefs and communities as tangible religare), the state’s dismissal of these to the privatist sphere may force the recourse to further symbolic action and this will be seen by some as a necessary risk. The alternative will be understood as responding as if the global religare of terror paradoxically legitimizes the unnecessary ornamentation of communal religious expression within the public sphere.

As Baudrillard notes, already the West is responding to “the spectre of terrorism” by terrorizing itself.49 In effect we are unsure how to respond to what he notes is the inversion of the master and slave relationship because the non-terrorist is “deprived of death and destiny” while the terrorists, the ones who control death, are the symbolic master.50 The western terrorising of “itself” occurs when, seeking to remain “tolerant” it provides the symbolic space for the terrorist “master” impose a hyper-real condition of REAL EVENT-DEATH as a permanent condition of the religare of fear and “eschaton expectation” – the “crystallization” of “all the ingredients in suspension”.51

The dilemma for the secular, cosmopolitan society is therefore when the private belief attempts to act within the public domain in a manner that seeks to impose its particular values and identity upon all within the society, this is particularly true of any recourse to religious fundamentalism. To avoid the self-terrorism that is the common response, perhaps in the end all private beliefs are to be equally unequal – and so exist in a form of oppositional equality. This is because in a Loosian-derived modernity, unnecessary ornamentation is itself the location of definition in a pluralist society. To proceed from locating all religious identity as unnecessary ornamentation is perhaps the only way to achieve equality, but also the groundwork toward the articulation of a pragmatic common narrative of modern identity. To privatize religion may protect an individual’s identity, but it may also impede it. So, on the one hand the state may attempt to reply to fundamentalist terrorism with indifference. But what about the terrorism of the state and the uncertainty that the state – terror relationship bring to any discussion of either?

X. Conclusion:

Jean-Luc Nancy, who raises the question of “what is to be done?” also offers a possibility which in its articulation of the necessity of the provisional possibility is a possible (non)solution:

Perhaps though, we know one thing at least: ‘What is to be done?’ means for us, how to make a world for which all is not already done (played out, finished, enshrined in a destiny), nor still entirely to do (in the future for always future tomorrows).52

This challenge sits against the claims of necessity and certainty, the dualist battle that “terror” and “the war on terror” encompass. That this is a war of rhetoric – a rhetorical war – is also beyond a doubt. This is a point acknowledged by Kevin Roberts, CEO Worldwide of SAATCHI & SAATCHI Ideas Company in his recent “presentation to various U.S. Defense Intelligence Agencies”.53 Robert’s claim was the need for the rebranding of the rhetoric of “the War on terror”, with the aim to create a new “loyalty beyond Reason”, what Roberts calls a Lovemark: “these are brands that make deep emotional connections with consumers. Passionate connections that go inside people’s lives and make a difference”. These are brands that have “High Love, High Respect” such as Harley Davidson, Apple and JFK. For Roberts “brand America” currently has “High Respect, Low Love”. His rebranding of “brand America” and of the “War on terror” is based on his “Lovemark” credo: “Mystery, Sensuality and Intimacy”. This could be termed the seduction, the eroticism of the brand, the pornography of global capital.

Roberts’ rebranding is to what he terms the “fight for a better world”, a fight launched alongside the war on terror that seeks to tackle geopolitical issues such as “global AIDS, malnutrition and malaria”. But Roberts’ call “to create America as a lovemark” is a response that needs to be added to the already empty rhetoric that “terror” inspires. This is capitalism as hyper-real benevolence, a simulacrum of compassion that is pushing a global product. It merely swerves to emphasise Zillah Eisenstein’s critique that: “Anti-terrorism rhetoric fits well with global capitalism …there is no single country that houses terrorism…or capitalism. Both are networked transnationally.54

What this demonstrates is that the religare, the religion of terror has already become just another product, something to be consumed in a form of globalization. Baudrillard encourages us to think about the problem of fundamentalist terrorism by reversing several of our standard assumptions. What if it were Islam, he asks, that were spreading through the West and rising to dominate the globe? Baudrillard tells us that if this were the case then “…terrorism would rise against Islam, for it is the world, the globe itself, which resists globalization”.55

What we need to consider, perhaps even confront, is the challenge that the religare of globalization is the religare of terror which is both product and consumption of capitalism and its other – terror. For terror is the inside of capitalism; that which acts as perhaps the “lovemark” of the inverted fight against the global. This link of religion, modernity and capitalism was noted by Marx in his call that “the criticism of religion is the prerequisite of all criticism”.56 One could perhaps invert and expand it and say also that “the religion of criticism is the prerequisite of all terror”. This dualism is what perhaps sits under all questions involving the modern, capitalist state and terrorism. Both the state and terror are built on certainties – yet both are certainties under attack from their other within the religare of the global. As Nancy has also noted: “Where certainties come apart, there too gathers the strength that no certainty can match.57

The collapse of certainty is perhaps the collapse of the real, or rather the collapse of the belief in the real, a collapse that forces a struggle to assert the claim of the real (terror/war on terror) over and against the uncertainty and the indifference that the collapse of the real engenders. As Baudrillard notes: “There is no corpse of the real, and with good reason: the real is not dead, it has disappeared.58

The unacceptability of terror is only as unacceptable as the religare of modernity, of the global, of global capital, as the drive to non-ornamentation. All are drives for the real arising out of claims of certainty as to the location and representation of the real. The religare of the real is the religion of terror – and of the war waged against it – a war of mutual rhetoric that by transgressive public religion/religare and public death affirm the Manichean centrality of modernity itself. Baudrillard’s aphorism that ”He does not have room for both the world and for its double – but no one knows which will have the last word”59 sits under any consideration of a response. Perhaps the only response is not to fall into the impatience of desiring a response, for out of impatience could possibility eventuate that which we do – but deny – desire:

Impatience is a millenarian passion which desires the immediacy of the end. Now today, wherever time has been abolished by the operation of ‘real time’, events no longer come to maturity, either immediately or with a delay. But impatience is not consoled by that: having nothing left to devour, it devours the remains of the real.60

The immediacy of the end, the desire to immediately end “terror/the war on terror” or that which terror strikes at, are reminiscent of the drive to hygiene of futurism, the banishing of ornament, the self-implosion of Modernity at Pruitt-Igoe. The state that desires the immediate end to terror by self-terrorising itself is itself devouring what it believes is the remains of the real (itself as bureaucratic state) out of a millennial passion for the end. This self-terror of the self-devouring response has, as Baudrillard notes, its immediate prior expression in the West’s hyper-real Iranian Fatwa it carried out for the Iranian state on Salman Rushdie: “The Iranian strategy consists in inflecting Western culture with fear, duplicity and self-pity”.61

Perhaps the issue is the centrality of the Loosian modernist rejection of disorder – a pursuit of order as religare that terror seeks to deny and discredit. Writing of the 1988 Libyan terror bombing of the plane over Lockerbie, Baudrillard notes: “What fascinates thought is this terrorist enchanting of things, the symbolic disorder of which terrorism is merely the visible epicentre”.62 The choice is therefore a degree of no-choice, the enchanting of terror by the state, the enchantment of terror by the terrorist, both symbolize a disorder against the Loosian claims of the realised real in ordered modernity, in the systems of order that the bureaucratic state now activates to self-terrorise itself, in effect to institute its internal Fatwas on its own citizens in the recognition that: “Every society must choose itself an enemy, but it must not try to exterminate it”.63 The state and the self-instituting terrorist act both have each other as enemy, but cannot act for a final extermination, a fulfilled millennial, apocalyptic passion for then their claims of and for the real are finished. The act of extermination is the internal destructive act of Pruitt-Igoe, the real terror is that turned by the state upon itself, to clear the space for the self-transcendence of its prior claim for the real.

As the French novelist Frederic Beigbeder notes in his mediation on the final hours of the twin towers: “Since September 11, 2001, reality has not only outstripped fiction, it’s destroying it. It’s impossible to write about this subject, and yet impossible to write about anything else. Nothing else touches us”.64 The Western Fatwa has been extended – we all now live as Rushdie: self-imprisoned not by the original action but by our (Western) reaction to the original event-death. The Irony is that the modern Western dismissal of the ornamentation of religion has been supplanted by a religare of terror that ornaments us continually in the hyper-real self-Fatwa. Maybe our best case scenario is to hope that Baudrillard is right when he says: “terror is dissipated by irony”65 Neither are in short supply today.

About the Author:

Mike Grimshaw is Senior Lecturer in Religious Studies, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand. He researches and publishes on the intersections of religion, theory, identity and location in the contemporary world and is completing a text Bibles & Baedekers: Tourism, Travel, Exile & God for Equinox Press, United Kingdom. He is author of “Soft Modernism: The World of the Post-Theoretical Designer” at Ctheory.net: http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=418

Endnotes

1 – Filippo Marinetti. “The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism” (c. 1908) Originally published in Le Figaro, Paris: 20 February, 1909. See: Hershel B. Chipp et. al., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968:284-286. Marinetti’s career reached its apogee in his friendship with the fascist dictator Mussolini.

2 – Tate Modern Art Museum (London, England). Century City Vienna 1908-1918: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis. An exhibition curated by Richard Calvocoressi and Keith Hartley, director and senior curator at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh: http://www.tate.org.uk/modern/exhibitions/centurycity/ (link no longer active 2019)

3 – Jean Baudrillard. This is the Fourth World War: The Der Spiegel Interview With Jean Baudrillard. International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Volume One, Number One (January 2004)

4 – Jean-Luc Nancy. “What is to be Done?” Translated by Leslie Hall. In Simon Sparks (Ed.) Retreating the Political. Phillipe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy. Routledge: London and New York, 1997:157-158, 157.

5 – Jean Baudrillard. “Information at the Meteorological Stage”. Liberation, September 18, 1995. In Jean Baudrillard. Screened Out. New York: Verso, 2002:85-86.

6 – Timothy Luke. “On 9.11.01”. TELOS: Symposium on Terrorism. Number 120, Summer 2001:134.

7 – Charles Jencks locates the death of modern architecture at the destruction of the Pruitt-Igoe Housing scheme in St. Louis, Missouri on July 15, 1972 at 3:32 p.m. (“or thereabouts”). See: Charles Jencks. The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. Revised Enlarged Edition. London: Academy Editions, 1978.

7.5 – Editor’s note: Long before the dynamiting in St. Louis and the arrival of the planes in New York, both Pruitt-Igoe and the World Trade Centre represented another kind of terrorism, architectural in origin. Pruitt-Igoe, considered by most to be unliveable, was designed by Minoru Yamasaki who was also the architect of the World Trade Centre in New York. Considering this interesting coincidence of fatal destruction one recalls Baudrillard’s assessment of the WTC: “…we can say that the horror for the 4,000 victims of dying in those towers was inseparable from the horror of living in them – of living and working in sarcophagi of concrete and steel”. Jean Baudrillard. Requiem for the Twin Towers, New York: Verso, 2002. For an interesting footnote to Yamasaki’s career see: Mariana Mogilevich. “ARCHITECTURE: Big Bad Buildings: The Vanishing Legacy of Minoru Yamasaki”. http://www.americancity.org/article.php?id_article=62 (link no longer active 2019)

8 -Jean Baudrillard. The Spirit of Terrorism (2nd Edition). Translated by Chris Turner. London: Verso, 2003:19, 23).

9 – Ibid.:81.

10 – Jean Baudrillard. Fragments. Cool Memories III 1991-1995. Translated by Emily Agar, Verso: London & New York 1997:133.

11 – Jean Baudrillard. The Transparency of Evil (c 1990). New York: Verso, 1993:43.

12 – Adolf Loos. “Ornament and Crime” [c.1908]. In Ludwig Munz and Gustav Kunstler (Eds.), Adolf Loos. Pioneer of Modern Architecture. Translated by Harold Meek. London: Thames and Hudson, 1966:226-231.

13 – Ibid.

14 – Thomas Altizer. The Gospel of Christian Atheism. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1966:22.

15 – Panayotis Tournikiotis. Adolf Loos. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994: 23.

16 – Filippo Marinetti. The New Religion-Morality of Speed [Futurist Manifesto, first number of L’Futalia Futurista May 11 1916]. In R.W. Flint, (Ed.) Marinetti: selected writings. Translated by R.W. Flint and Arthur A. Coppotelli. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1972: 94-96; 94.

17 – Ibid.: 96.

18 – Ibid.: 95.

19 – Ibid.: 95-96.

20 – Jean Baudrillard. Fragments. Cool Memories III 1991-1995. Translated by Emily Agar. Verso: New York, 1997:75.

21 – Adolf Loos. “Ornament and Crime” [c 1908]. In Ludwig Munz and Gustav Kunstler (Eds.). Adolf Loos. Pioneer of Modern Architecture. Translated by Harold Meek. London: Thames and Hudson 1966:226-227.

22 – Ibid.: 229.

23 -Adolf Loos. “Ornament and Crime” [c 1908]. In Ludwig Munz and Gustav Kunstler (Eds.). Adolf Loos. Pioneer of Modern Architecture. Translated by Harold Meek. London: Thames and Hudson, 1966:227.

24 – Jean Baudrillard. Paroxysm. Interviews with Phillipe Petit. Translated by Chris Turner, Verso: New York 1998:50.

25 – Adolf Loos. “Ornament and Crime” [c 1908]. In Ludwig Munz and Gustav Kunstler (Eds.). Adolf Loos. Pioneer of Modern Architecture. Translated by Harold Meek. London: Thames and Hudson, 1966:230.

26 – BBCnews.com. “Bin Laden Tape: Text”. Posted: Wednesday, February 12, 2003, 00:56 GMT. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/2751019.stm

27 – For my discussion as to what I have described as “soft modernism”, see Mike Grimshaw: “Soft Modernism: The World of the Post-Theoretical Designer” Ctheory.net: http://www.ctheory.net/text_file.asp?pick=418

28 – See: www.destinychurch.org.nz

29 – A Maori ceremonial posture dance accompanied by chanting (OED).

30 – Jean Baudrillard. The Spirit of Terrorism (2nd Edition). Translated by Chris Turner, London/New York, Verso 2003:37.

31 – Ibid.:44.

32 – Ibid.:46.

33 – During the past decade, activists who claim to represent the interests and concerns of the indigenous Maori people of New Zealand have undertaken a series of symbolic actions in an attempt to bring concerns regarding land rights, governmental policy as constituted under the Treaty of Waitangi (signed between Maori and the British Crown in 1840) and issues of claims for Maori sovereignty (tino rangatiratanga see http://aotearoa.wellington.net.nz/ (link no longer active 2019)) into the public arena. Their actions have tended to be highly symbolic manifestations directed at symbols of New Zealand’s colonial legacy – or as in the America’s Cup, issues of a capitalist-driven nationalism. The Pine tree on One Tree Hill in Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city, was viewed by Maori as a symbol of colonial oppression. Originally an indigenous Totara tree was on the spot, but this was replaced in the nineteenth century by Pine trees, which over time, were reduced to the singular iconic Pine. The tree had gained an international recognition with the song “One Tree Hill” on the rock group U2’s 1987 album The Joshua Tree; a song written about that particular tree as an icon. In the 1990s a group of Maori activists occupied an area known as Moutoa gardens in the small North Island city of Wanganui over land rights grievances. As part of this protest, a statue of the colonial Premier John Ballance, standing in the gardens, was symbolically decapitated. In 1997, there was a further act of symbolic destruction undertaken by a Maori nationalist. In this, the Americas Cup for international yachting (a competition dating to 1851) was attacked. The protest was undertaken as a means of highlighting indigenous rights to an international audience – and caused (US) $27,000 damage. This attack was covered by both CNN and The New York Times. In 1997 the activists Tama Iti and Te Kaha stole a triptych painting (the Urewera mural) from the Department of Conservation centre in the Urewera National Park. The painting, by New Zealand’s premier artist Colin McCahon, was valued at over (NZ) $1 million. The theft was another attempt to bring issues of Maori nationalist concern to a wider audience. After 15 months the painting’s return was negotiated. Lastly, in 2005, the activist Tama Iti led a series of symbolic challenges to a visiting legislative body, the Waitangi Tribunal, when they entered his tribal lands for a land rights hearing. The challenge reached its climax when he discharged a double-barrelled shotgun into the New Zealand flag, which had been thrown onto the ground in front of the Tribunal. In all these cases, the response was to treat them as acts of criminality. This was partly due to a state of heightened race relations in New Zealand over the past decade, and I believe, a determination to use the language of criminality in an attempt to disempower the symbolic recourse.

34 – Jean Baudrillard. The Spirit of Terrorism (2nd Edition). Translated by Chris Turner, London/New York, Verso 2003: 58. Editor’s note: A recent example of this attitude is the shooting by police of an innocent Brazilian man in the London subway following the London bombings, on July 22 2005. The police response was that such a mistake, while regrettable, may indeed occur again, due to the heightened “state of terror”.

35 – Ibid.:81.

36 – G. Clarke Chapman Jr. “Terrorism. A problem for ethics or pastoral theology?” Crosscurrents Spring 2004:120-137, 123.

37 – Georges Bataille. Georges Bataille: essential writings. Michael Richardson (Ed.), London: Sage, 1998:53.

38 – ibid.:55.

39 – ibid.:56.

40 – Ibid.:58.

41 – Ibid.:62-63.

42 – BBCnews.com. “Transcript of Bin Laden Video Excerpts”, Posted: Thursday, December 27, 2001, 19:57 GMT. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/1729882.stm

43 – Georges Bataille. Georges Bataille: essential writings. Michael Richardson (Ed.), London: Sage, 1998:63.

44 – Ibid.:63.

45 – Slavoj Zizek. Welcome To The Desert Of The Real! Five Essays on September 11 and related dates. London: Verso, 2002:5.

46 – Paul Piccone and Gary Ulmen. “Introduction”, in TELOS. Symposium on Terrorism. Number 120, Summer 2001:4.

47 – Jean Baudrillard. The Spirit of Terrorism (Original in Le Monde: November 3, 2001) in TELOS. Symposium on Terrorism. Number 120, Summer 2001:134-142, 138.

48 – BBCnews.com. “Bin Laden Tape: Text”, Posted: Wednesday, February 12, 2003, 00:56 GMT. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/2751019.stm

49 – Jean Baudrillard. The Spirit of Terrorism. Translated by Chris Turner. New Edition. London: Verso, 2003:81.

50 – Ibid.:70.

51 – Ibid.:59.

52 – Jean-Luc Nancy. “What is to be Done?” [Translated by Leslie Hall] in Simon Sparks (Ed). Retreating the Political. Phillipe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy. Routledge: London and New York, 1997:157-158, 157.

53 – Kevin Roberts. “Loyal Beyond Reason”. New York, March 9, 2005. www.brandweek.com/brandweek/photos/2005/09/20050919RobertsSpeech.pdf (link no longer active 2019)

54 – Zillah Eisenstein. Against Empire. Feminisms, Racism and the West. New Delhi: Women Unlimited Press, 2004:8.

55 -Jean Baudrillard. The Spirit of Terrorism. New York: Verso, 2002:12.

56 – Karl Marx. “Introduction to A Contribution to The Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right”, February 1844.

57 – Jean-Luc Nancy. “”What is to be Done?” Translated by Leslie Hall. In Simon Sparks (Ed.), Retreating the Political. Phillipe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy. Routledge: London and New York, 1997: 157-158, 158.

58 – Jean Baudrillard. Fragments. Cool Memories III, 1991-1995. Translated by Emily Agar, Verso: London and New York, 1997:141.

59 – Ibid.

60 – Ibid.:125.

61 – Ibid.:81.

62 – Jean Baudrillard. Cool Memories II, 1987-1990. Translated by Chris Turner. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1996:21.

63 – Ibid.:61.

64 -Frederic Beigbeder. Windows on the World. A Novel. Translated by Frank Wynne, Fourth Estate: London, 2003:8.

65 -Jean Baudrillard. Seduction (c 1979). Montreal: New World Perspectives, 1990:128.