ISSN: 1705-6411

Volume 3, Number 1 (January 2006)

Author: Dr. Edward Scheer

Death

Those things once clung to us like our skin, and this is how our property still clings to us today. We are contained in nothing and photography assembles fragments around a nothing.1

Jean Baudrillard. Saint Beuve, 1987

We can be drawn so deeply into the image, out of our own histories and into another’s in a way which prefigures our own mortality, “an awareness of a history that does not include us” as Miriam Hansen says of Benjamin.3 Barthes’ and Benjamin’s writings on photography also resonate with this curiously benign sense of death as the great blind spot that gives shape and meaning to our images and our histories. For Baudrillard it is the object itself in its desire to become image that hurries to its oblivion in the photograph, an oblivion shared by the photographer:

If something wants to become an image, this is not so as to last but in order to disappear more effectively. And the photographing subject is a good medium only if s/he joins in the game, exorcises his/her own gaze and judgement, revels in his/her own absence.4

The blink of an eye (or a shutter) blots out the world and the gaze for just a moment, the syncope, the little death starts the machinery of mnemonic performance which results in the photographic image.

Jean Baudrillard. La Bocca, 1998

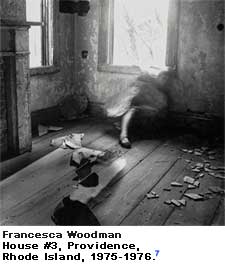

Photography for Baudrillard is not about appearances but disappearances, of the subject, the object and reality itself. But this is of course a particular photography based in the action of a direct inscription rather than a chemical or digital process.5 Is the perception of photography as a disappearing act altered by the perception of the disappearance of traditional photography as the disappearance of photography? As Geoff Batchen has said: “The suggestion is that a diminution of our collective faith in the photograph’s indexical relationship to the Real will inevitably lead to the death of photography as a distinctive medium”.6 The problematics of photography’s capacity for direct inscription, the cultural ubiquity of the image, the development of digital imaging techniques and the expansion of virtual reality worlds all contribute to this sense of the end of the photographic, though Batchen argues that photography has been rehearsing its death for some time. He draws attention to the tradition of mourning photographs of another time and even Benjamin’s much discussed death of the auratic in the age of photo-mechanical reproduction. More recently one could add Francesca Woodman’s haunting images of her body disappearing from the frame presaging her own suicide. Peggy Phelan says of these images that they establish the manner in which her death survives her work.

II. Abreactions

Francesca Woodman. House #3.7

But if traditional photography is dead where can this absence, this sense of loss be registered? Digital technologies surely cannot provide guaranteed repositories for memory, nor are they adequate substitutes and we cannot confide in such an abstract process so devoid of physical engagement with the world. But neither can we trust the photograph, the accidental artefact of such an engagement. In any case the arrogance of the image in taking the place of our memories is intolerable. Images, virtual or analogue, cannot be trusted. The question becomes one of actions. In what does our image making performance consist? If we cannot act out our fear of death in virtual space then perhaps this and this only is where the function of the photograph endures and survives the death of the photographic image. In his essay, “It is the Object Which Thinks Us”8 Baudrillard the philosopher and eschatological prankster, describes the photograph itself in its “happier moments” as an “acting out on the world, a way of grasping the world by expelling it”,… (a)n “abreaction of the world”.9 Here the image gaily expels the demons of the world, merrily discharges the affects associated with the trauma of living. So far so good, but there is a history to this term which bears some further reflection.

The term abreaction, itself comes from Freud’s early work with Breuer and published in the paper On the psychical mechanism of hysterical phenomena: preliminary communication of 1893. Freud and Breuer argue for the necessity of reactions adequate to traumatic events as a way of discharging the affect provoked by these traumatic episodes. Stifled reactions may need to be “abreacted” later on.10 Abreaction appears here for the first time as the active constituent of catharsis. More precisely it denotes the end state of a process of “living out” or “acting out” a “previously repressed experience” with the attendant discharge of affect.11 In the clinical application of abreaction the events in the patient’s repressed memory are precipitated and re‑rehearsed in order to de‑potentiate “the affectivity of the traumatic experience”.12 The process involves the simultaneous action and activation of memory with the anticipation of future trauma.

This kind of future anterior movement to abreaction, the anticipation of future trauma and a desire to head it off coupled with a mnemonic performance, a going back over old ground to smooth the way for the future, is an ongoing process. But this movement of abreacting also recalls Barthes’ understanding of the time of the photograph, the simultaneity of the “this will be” and the “this has been” and their co-presence in the one representation.13 The photograph occurs in this liminal time, this synaptic time, the spasm in which the present is stolen away. The “thunderstruck effect” as Baudrillard puts it.14 One might argue that what the photograph performs in relation to time is what abreaction performs in relation to the subject. The syncope in which it loses itself in order to regain itself for a presupposed future. Abreaction is always in process, a catharsis neither achieved nor desired. In this sense abreaction is also a feature of Baudrillard’s writing: the drama of inversions and doubles, of repetitions and intensities, the acting out of impossible events, the mise en scène of the other. Fatal strategies, cruel poetics, snapshots of the time – his writing is another photography. In the production of his images, we encounter a different order of abreaction.

III. Photographic Abreactions

And it is quite clearly not a matter of the photography of abreaction in which emotions are acted out and discharged for the benefit of a camera. There is of course a history for this too which reinforces the distance separating Baudrillard’s photography from his writing. The earliest example of this genre is Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne de Boulogne in his study, Mécanisme de la Physiognomie Humaine of 1862 which sought to capture in image and text the nexus between facial muscular configurations and the emotions. Duchenne worked at Salpetrière with neurological patients and developed treatments based on the notion that the conditions he encountered were related to electrical dysfunctionality in the nervous system. He used electrical current to stimulate neural activity and in the process realised he could isolate individual groups of muscles and cause them to contract.

Dr. G.B. Duchenne. Electrization, 1862 15

This subject shown above had an anaesthetic condition of the face which made it possible to stimulate some muscles without generating involuntary responses from others. Duchenne likened it to “working with a still irritable cadaver”.16

O.J. Rejlander. Ginx’s baby

The photographs he took of his experiments show electronic muscle stimulation used on the facial muscles to reproduce reproduced or re-enacted emotions.17 These photographs used in Duchenne’s text would themselves become influential a decade later for Charles Darwin in his proto-ethological treatise, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Darwin includes a number of these images in his text, along with some others by the photographer O.G. Rejlander.18 Perhaps the most famous of these images is the photograph called “Ginx’s baby” showing the detailed features of a baby in the action of crying”.19 This image was said to have “scattered to the winds” previous representations of the emotions. What it actually shows is that the emotions are always partly a matter of the imagination and the intentions (creative or habitual) of individuals and that the photograph at its very origin was an unreliable witness. Here it is the imagination of the eager Oscar Rejlander, keen to help Darwin establish a case for his reading of emotional expressions. His interventions make the image clearer but muddy its significance.20 Rejlander’s actions remind us that emotions and photographs are always part performances. Their representation is never simply a matter of transcription but rather of reinscription and invention, of abreaction.

O.J. Rejlander. Surprised Person.

In some of the images Rejlander himself acts out the emotion Darwin is describing participating as actor and photographer. An all too evident case of the idea that Baudrillard describes as endemic to the photographic act: “perhaps even, in the photographic act, the world itself maybe acting out, foisting its fiction on the subject… and … sets up a material collusion between the world and ourselves, in so far as the world is a continual acting out”.21 The hyperactive semiosis of these images is perhaps too graphic, too theatrical an illustration for what is a generalised and quotidian feature of the performance of everyday life. In any case, is this extravagant gesture really what surprise looks like? “Every face” Baudrillard says, “is already an acting out…”.22

Jean Baudrillard, 1993.

The visible, contrary to what Joyce23 says, is not an ineluctable modality. It always speaks or is spoken for. Here at the end of the history of the photograph, a philosopher who hastened the end of a modernity based on stable representational systems declares himself a photographer. That is, a participant in the abreacting of the world through – let’s repeat it – the precipitation in a representation and the intensive repetition of a problematic experience, the subsequent appropriation of its power and negation of its influence. Isn’t the power of the photograph precisely this appropriation of the power and influence of that which troubles us and haunts us most…? This death at the heart of the image which Barthes named the punctum.

Jean Baudrillard. St Clément, 1987

What we have in Baudrillard’s photography is an acting out again of the rituals of the image. I was there. I saw this which my photograph recalls like a talisman. These photos represent, we are told, the inarticulable, yet we know them through the writings of their progenitor. They are mannered, beautiful, structured. They look like works of art. But haven’t we finished with works of art? I thought Artaud had put that one to bed, “en finissent avec les chefs d’oeuvres” and Baudrillard is a scholar of Artaud as well as a profoundly Artaudian scholar as Alan Cholodenko has recently argued.24 And what does Artaud tell us about the image? “My drawings are not drawings” he says. They are documents of a process which wants to disestablish aesthetic judgement and perception by abrasively acting them out. They are, in short, abreactions of the “system of fine arts”.25

Only now, when the photograph has its own problems, its own crisis, Baudrillard takes up his camera to belatedly assist in the abreaction of the photographic image, revealing again his complicity with the evil demon. These images insist on a relation between objects and images, demand a representational arrangement, restore referent and copy to their natural historical association. But isn’t this unnatural in the digital age? Baudrillard is always untimely, either speaking slightly ahead of us or returning us to an earlier version of ourselves. Upbraiding our fossils and our clones as he says in regard to the end of the film Jurassic Park.

IV. Ecstacy of the Photograph

“The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new”.26 We cannot help ourselves. More and more images are projected onto the already bloated corpse of photography. In Baudrillard’s description of what he calls “fascinating obesity”, “it is neither the compensatory obesity of the underdeveloped nor the alimentary one of the over nourished. Paradoxically, it is a mode of disappearance for the body”.27 One might say the same for photography. Everywhere space is rounded out by the image. The world is already saturated with them. Yet Baudrillard argues for the photograph by suggesting that the world itself is self-evident, that the photograph masks this suffocating redundancy of the world. But on what basis is the separation of world and image justified? You do not have to go to Times Square or Shibuya to notice this effective interpenetration of physical space and image space. Once you could have just read about it in Baudrillard. Does his later incarnation as an image maker require a double take on his writing or are the images already spoken for by a voice we know?

Looking at the images listening at the same time for the voice, we wonder, where is the joke, the punch line, the ironic reversal? There seems to be another Baudrillard emerging through these photographs, the trickster whose last gag is this series of beautiful images. He has outsmarted us all. The art of this postmodernist is not after all postmodern. These are not simulations. They seem to forget what their author told us about them. They are naturalistic images which we see through the complex and refractory gaze of a writer who changed the way we look at the world only to ask us to change again and to look back.

These images are pictures, not copies, to use Benjamin’s distinction. He describes the copy as “the stripping bare of the object, the destruction of aura”, which he says, “is the mark of a perception whose sense of the sameness of things has grown to the point where even the singular the unique, is divested of its uniqueness, by means of its reproduction”. Here the copy is opposed to the picture and the qualities of “transience and reproducibility” are opposed to those of “uniqueness and duration”.28 Baudrillard’s photos, though clearly reproducible are not disposable. They leave a mark, a shadow of being.

Jean Baudrillard. Punto Final, 1997.

But of course Benjamin and Baudrillard the writer are in stark opposition on the topic of the photographic image. Benjamin’s sensuous reapprehension of the world through the optical unconscious of the image is anathema to Baudrillard the writer, who argues that the senses are subordinated to the essential disembodiment of the image, “to make an image of an object is to strip the object of all its dimensions one by one: weight, relief, smell, depth, time, continuity and of course meaning… to add back all these dimensions… is where images are concerned utter nonsense”.29 Similar language to Benjamin but Baudrillard is talking of the image in general.

In his photos maybe we can see a process of picturing the mimicry of mimicry. A process which ends, as Darwin’s writing proves, in the reassertion of the priorities of the natural. Accounting for this dissymmetry Michael Taussig says:

No matter how sophisticated we may be as to the constructed and arbitrary character of our practices, including our practices of representation, our practice of practices is one of active forgetting such mischief each time we open our mouths to ask for something or to make a statement. Try to imagine what would happen if we didn’t in daily practice thus conspire to actively forget what Saussure called ‘the arbitrariness of the sign’? Or try the opposite experiment. Try to imagine living in a world whose signs were indeed ‘natural’.30

Darwin’s aim in his The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals was of course precisely this, to locate and define those universal emotional signs (shrugging the shoulders, blushing etc.) which would prove transcultural and therefore natural. It is a logic which, he argues, demonstrates the work of evolution: “the conclusion that man is derived from some lower animal form”.31 The photographs he employs as evidence are in fact, mostly, elaborate performances and constructions and as such are entirely artificial. In this sense they suggest the impossibility of the larger argument.

Baudrillard’s images for their part are much more natural, suturing the gaze into the landscape of the image without formal effects. From the evolution of behaviours to the evolution of the image, Baudrillard’s photos recall a mythic photographic age of uncomplicated referentiality, the kind of representation that Darwin needed but did not get out of Rejlander and Duchenne. They are an abreaction of the photograph, a traumatised re-enactment of the forgotten, repressed, perhaps even fictional earlier stages of the photograph, when it was an image stolen from the world. They enact a doubled anamnesis like Chris Marker’s “photo roman” la Jetee of 1962, an abreaction of memory itself: “This was the purpose of the experiment, to throw emissaries into time, to call past and future to the rescue of the present”.32

These images activate a mnemonics of a being there of a subject, Baudrillard, but not the being of the photograph. As photographs they actively forget themselves. As Lotringer has recently argued, “For Baudrillard the actual photographs are beside the point. It is what precedes them that counts in his eyes – the mental event of taking a picture – and this could never be documented, let alone exhibited”.33 This understanding of photography as a mental event affirms the performativity of these images but denies their mediation, their framing of actions in the world.

The photographs are windows onto a moment that does not seem to be the present. They are neither violent nor hysterical. There is nothing in them of the postmodern affirmation of the materiality of the signifier or the pastiche of the cultural commodity. Except perhaps there is the sense, occulted away within them, that he knows that we know that we’ve been here before, seen these things before in precisely this way. This kind of photography we know so well as to take it for granted. Our images of ourselves we wear like a second skin though we know how dissembling they are. We actively forget this function of the image to hide ourselves from ourselves. These photos are not postmodern but perhaps they represent an acting out again of the face of photography itself. As he says,

Every face is already an acting out. You expel and expose your life through the features of your face, or of your body, or your writing… To find the photographic act equivalent to this acting out, this expulsion of facial features, which is very different from psychological expression, is certainly the most delicate of operations.34

Abreaction is a work of anamnesis which is designed to assist in the integration of experiences into a subject’s memory and then perhaps only in order to, eventually, help them forget. Perhaps, after all, Baudrillard’s abreactions are performed to help us forget the trauma of the death of photography. A death which, as he says, “enfolds the image” as in this series of images assembled around a nothing, a punctum, a death which survives in the work of the photograph. For Baudrillard, post-photographic practices enact the death of the punctum itself, which is the poignant nothing at the centre of the image, but lost to both time and the viewer. It is this death of the death at the heart of the photograph which haunts him and which he fears will be “lost in the automatic proliferation of images”.35 And it is this to which these images respond. Abreacting death, the culmination of all abreactions and one of the more visible modalities of the impossible is “certainly the most delicate of operations”. These images finally remind us of what lies ahead: “And we must struggle against the possibility that we will not die”.36

About the Author:

Edward Scheer is an Artaud scholar with an interest in multimedia technology and post-structuralist theory. He is editor of 100 Years of Cruelty: Essays on Artaud. (Sydney, 2000) and Antonin Artaud: A Critical Reader (London and New York, 2004). He has published on performance forms as diverse as butoh, narrative theatre and performance art as well as time based arts and television. More recently he has focused on the study of cybernetic performance and the emotions. He is a long serving member of the board of directors of Performance Space Sydney. He has also written extensively for the Good Weekend and the “Spectrum” section of the Sydney Morning Herald.

Endnotes

1 – Siegfried Kracauer. “Photography” (c. 1927). Translated by Thomas Y. Levin. Critical Inquiry, Volume 19, Number 3, Spring 1993:421-436.

2 – Baudrillard’s photographs appearing in this article are included in: Jean Baudrillard. Photographies 1985 – 1998. Peter Weibel (Ed.), Hatje-Cantz and Neue Gallery, Graz, 1999.

3 -Miriam Hansen. “With Skin and Hair: Kracauer’s Theory of Film, Marseilles 1940”. Critical Inquiry, Volume 19, Number 3, Spring 1993:456.

4 – Jean Baudrillard. Photographies 1985 – 1998. Peter Weibel (Ed.), Hatje-Cantz and Neue Gallery, Graz, 1999:129.

5 – He has similar feeling for computers and the digitalization of writing: “There is… nothing more contrary to thought and writing than their real-time operation on a screen or a computer”. See Jean Baudrillard, Paroxysm, New York: Verso, 1998:31.

6 – Geoff Batchen. “Post-Photography: After but not yet beyond”. In Blair French (Ed). Photo Files: An Australian Photography Reader. Power and ACP: Sydney, 1999:227.

7 – Francesca Woodman et. al. Francesca Woodman. Zurich: Scalo and Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporarien, Paris, 1998. See : http://www.heenan.net/woodman/41fwdmn.shtml (link no longer active 2019)

8 – Jean Baudrillard. Photographies 1985 – 1998. Peter Weibel (Ed.), Hatje-Cantz and Neue Gallery, Graz, 1999.

9 – Ibid.:146.

10 – Sigmund Freud and Joseph Breuer. “Studies on Hysteria” in The Pelican Freud Library, Volume Three. Edited and translated by James and Alix Strachey. London: Pelican Books, 1974:59‑62.

11 – S. Walford‑Skinner. A Dictionary of Psycho‑Therapy. London, New York: Routledge, 1986:2.

12 – Carl Gustav Jung. “The Therapeutic Value of Abreaction.” In his Collected Works, Volume 16. London: Routledge, 1967:130‑33. For Jung, the problem is not the affectivity associated with a traumatic episode so much as the dissociation of the psyche which it engenders. The task of abreaction as he sees it is therefore to “reintegrate the neurotic dissociation” permitting the incorporation of the traumatic moment into the conscious mind as “accepted content” (131). Jung also mentions the danger implicit in this method arising at the moment of recall which can result in a cathartic inversion, accentuating the symptoms rather than relieving them. This may occur even if effective emotional discharge occurs. However the principal reason for Jung’s dismissal of abreaction as a therapy is due to the difficulty of substantiating traumatic aetiology. Interestingly, Jung also suggested an amendment to Freud’s original theory to include the relegation of “the determining cause” to “the patient’s pre‑natal life” (130).

13 – Roland Barthes quoted in Geoff Batchen, “Post-Photography: After but not yet beyond”. In Blair French (Ed). Photo Files: An Australian Photography Reader. Power and ACP: Sydney, 1999:232.

14 – Jean Baudrillard. “For Illusion Isn’t The Opposite of Reality”, In: Jean Baudrillard. Photographies 1985 – 1998. Peter Weibel (Ed.), Hatje-Cantz and Neue Gallery, Graz, 1999:134.

15 – See: http://chem.ch.huji.ac.il/~eugeniik/history/duchenne.html (link no longer active 2019)

16 -Charles Darwin. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Third Edition. Richard Ekman (Ed.), Oxford University Press, 1998:405

17 – Duchenne was a kind of 19th Century Stelarc, the Australian artist who employs similar methods in his performance art today. See: http://www.stelarc.va.com.au/ (link no longer active 2019)

18 – The images were heliotypes which enabled mass reproduction. Heliotyping involves “coating a printing plate with light-sensitive gelatin emulsion, which is exposed photographically using an ordinary negative. The gelatin emulsion reticulates, or develops tiny fissures, in a pattern corresponding to the negative used. These fissures form a relief copy of the photographic image on the plate, which can be inked and run through a printing press using ordinary paper stocks”. (Phillip Prodger in Charles Darwin. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Third Edition. Richard Ekman (Ed.), Oxford University Press, 1998:401). Prodger argues that Muybridge and Marey were influenced by these images and both in turn influenced the development of the moving image.

19 – It has recently emerged that this is not actually a photograph at all but a “photographic copy of a drawing after an original photograph” (Ibid.:147).

20 – Ibid.

21 – Jean Baudrillard. “It is the Object Which Thinks Us”. Photographies 1985 – 1998. Peter Weibel (Ed.), Hatje-Cantz and Neue Gallery, Graz, 1999:146.

22 – Ibid.

23 – See: James Joyce, Ulysses (c 1922), New York: Penguin 1984: 42, where he refers to the: “Ineluctable modality of the visible”.

24 – Alan Cholodenko. “The Logic of Delirium, or the fatal Strategies of Antonin Artaud and Jean Baudrillard”. In Edward Scheer (Ed.) 100 Years of Cruelty. Essays on Artaud, Sydney Power and Artspace, 2000:153-174.

25 – Edward Scheer. “Sketches of the Jet: Artaud’s Abreaction of the System of Fine Arts”. In Ibid.:57-74. Baudrillard does so while his own photographs are being taken into galleries and museums. See: Sylvere Lotringer. “The Piracy of Art”. International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Volume 2, Number 2, (July 2005).

26 – Samuel Beckett. Murphy. London: Calder and Boyars London, 1970:5.

27 -Jean Baudrillard. “The Obese” in Fatal Strategies, Translated by Philip Beitchman and W.G.J. Niesluchowski. New York: Semiotext(e)/Pluto, 1990:27.

28 – Walter Benjamin. “A Small History of Photography” One Way Street and Other Writings. Translated by Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter. London: Verso 1979:250.

29 – Jean Baudrillard. “It is the Object Which Thinks Us”. Photographies 1985 – 1998. Peter Weibel (Ed.), Hatje-Cantz and Neue Gallery, Graz, 1999:130.

30 – Michael Taussig. Mimesis and Alterity. A Particular History of the Senses. New York, London: Routledge, 1993:xvii, xviii.

31 – Ibid.:360.

32 – Chris Marker. La Jetée. Argos Films, 1962.

33 – Sylvère Lotringer. “The Piracy of Art”. International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Volume 2, Number 2, July 2005.

34 – Jean Baudrillard. “It is the Object Which Thinks Us”. Photographies 1985 – 1998. Peter Weibel (Ed.), Hatje-Cantz and Neue Gallery, Graz, 1999:146-7.

35 – Ibid.:151.

Editor’s note: It may also be the case that what Baudrillard most fears in the contemporary is the loss of the joy of living. His is a joyful wisdom. If we write for the joy of it perhaps we also take photographs for their sheer pleasure:

People are always calling me ‘melancholic, despairing, a purveyor of nothingness, a mortician’. I’m tired of it. It is such a misunderstanding, or deliberate distraction; on the contrary, writing has always given me pleasure. It’s essential, it’s not at all despairing, just the reverse. One recourse seems to me to have been open: never to abandon language but to guide it in the direction where it can still utter without having to signify, without letting go what’s at stake, bringing illusion into play (Interview with Le Journal des Psychologues (1991), in Mike Gane, Baudrillard Live. New York: Routledge, 1993:179).

36 – Jean Baudrillard, The Vital Illusion (The Wellek Library Lectures). Julia Witwer (Ed.), Boston: Harvard University Press 2001:5.